In an interview with InvestmentNews, Flat Rock Global CIO Shiloh Bates explains why financial advisors may want to consider Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) in client portfolios.

19

Dec

2024

In an interview with InvestmentNews, Flat Rock Global CIO Shiloh Bates explains why financial advisors may want to consider Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) in client portfolios.

Shiloh Bates talks to the Bank of Montreal’s Head of CLO Trading, Bilal Nasir. In this episode, Bilal uses the term “risk profiles” to describe the different characteristics of various CLO investment opportunities. If you’ve ever wondered about the ins and outs of CLO trading, this is the episode for you.

Like & Subscribe: Amazon Music | Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Flat Rock Global CIO Shiloh Bates talks to Giovanni Amodeo, Chief Influencers Officer at ION Analytics about Collateralized Loan Obligation (CLO) markets, CLO equity, and BB notes.

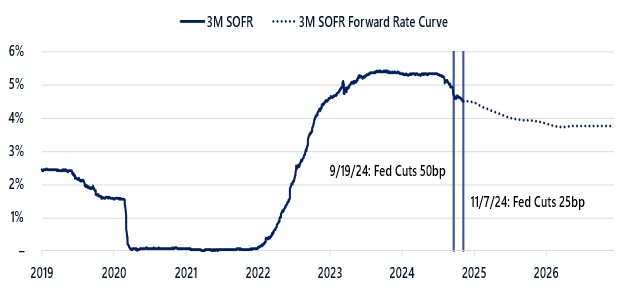

In September 2024, the Federal Reserve began its rate cutting cycle with a 50bps cut, followed by an additional 25bps cut in November. Market expectations, as reflected by US interest rate futures, anticipate further rate cuts in December and throughout 2025. The Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR), which serves as the base rate for private credit and CLOs, closely tracks the Federal Funds Rate. The SOFR forward curve represents the market’s expectations for future rates, where interest rate professionals can swap floating rate payments to a fixed rate. Declining SOFR may have different effects on the asset classes important to me: private credit loans, CLO BBs, and CLO equity.

Note: All data as of 11/11/2024. Source: Bloomberg, Intex Solutions.

Private credit loans typically reset their SOFR base rate every 30 to 90 days. As SOFR declines, lenders receive lower interest payments. However, even at 3.75% SOFR, the trough level on the SOFR curve, a middle market loan with a 5.0% spread would still yield 8.75%. I would consider this a compelling yield, as the loan is a senior and secured obligation of the borrower.

While lower loan income is negative for a lender, lower base rates may have some positive effects:

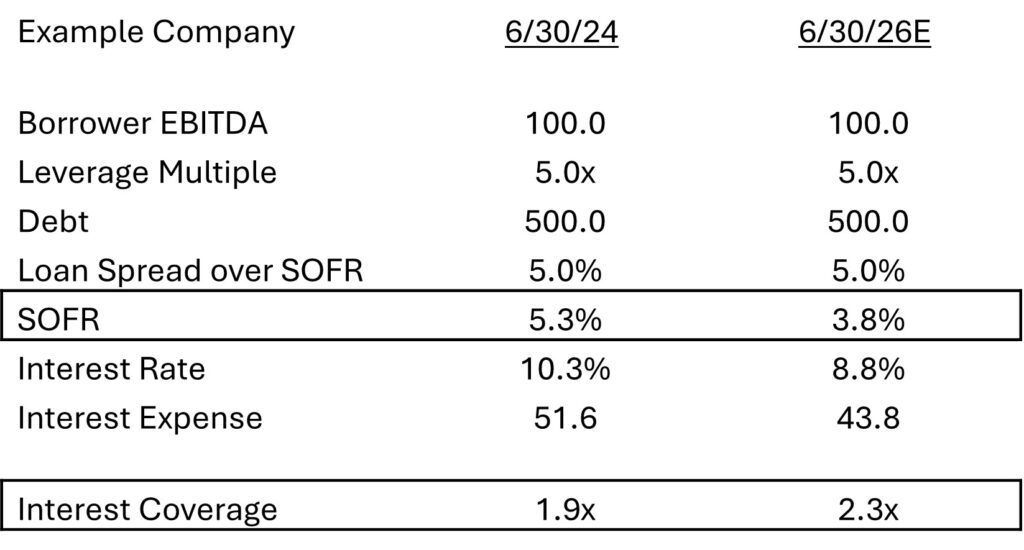

1.) Fewer Loan Defaults. Lower interest rates could decrease the frequency of loan defaults. To illustrate this, let’s examine a case study comparing interest burdens at two critical junctures: 6/30/2024, when SOFR was near its peak, and 6/30/2026, when SOFR is projected to hit a trough. In this example, the reduction in interest rates results in a nearly $8 million boost to the borrower’s cash flow. This improvement is reflected in the interest coverage ratio, a key metric measuring a borrower’s cash flow earnings (EBITDA) relative to annual interest expense, which increases from 1.9x to 2.3x. While most borrowers have managed to meet their interest payments even during periods of higher base rates, the projected decrease in rates could be crucial for others. For businesses operating with higher leverage, it could very well mean the difference between survival or default.

Source: Bloomberg, Flat Rock Global.

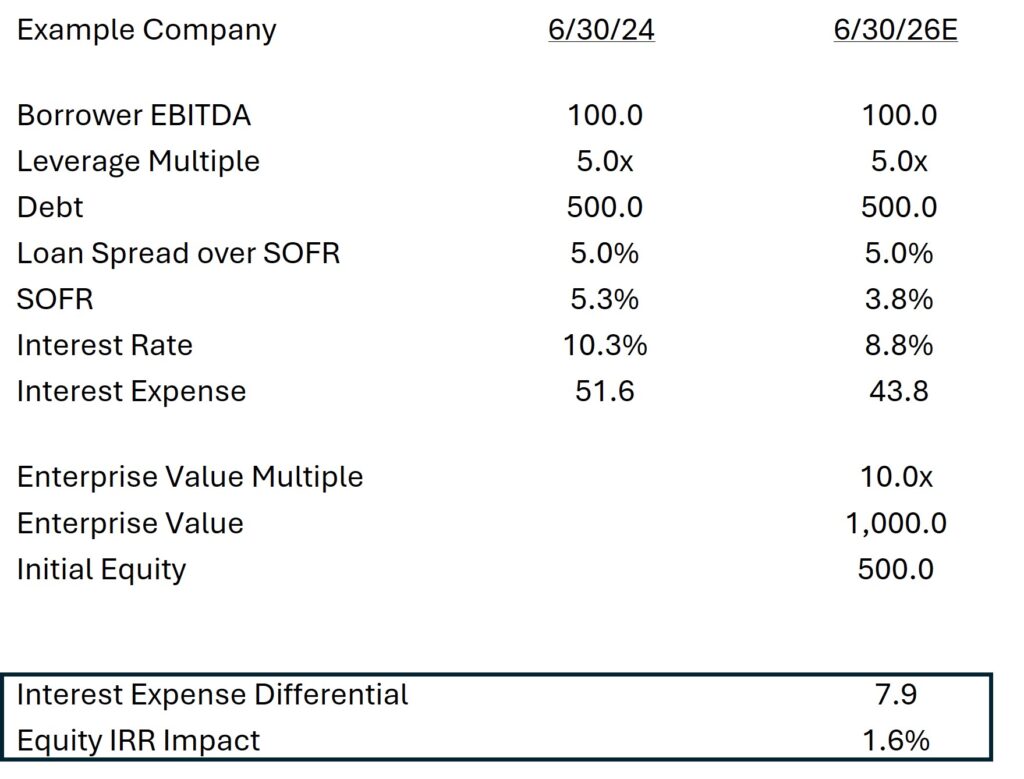

2.) Impact on Leveraged Buyout (LBO) Activity. The rise in interest rates in early 2022 had a significant effect on LBO activity. As loan financing became more expensive, LBO transactions saw a sharp decline. This slowdown resulted in a substantial accumulation of uninvested private equity capital, reaching approximately $2.1TL.1 If interest rates decrease as anticipated, I’d expect to see

a. Enhanced Private Equity Returns. The lower cost of borrowing could potentially boost private equity returns by approximately 1.6%.

b. Revival of LBO Activity. A more favorable interest rate environment may stimulate LBO transactions, creating additional loan opportunities for private credit investors.

Source: Bloomberg, Flat Rock Global.

CLO equity cash flows are primarily driven by the spread between the interest earned on the underlying loan portfolio and the financing cost of the CLO’s debt.

CLO equity is considered unlevered (however it does benefit from the overall leverage of the CLO), and lower base rates typically reduce CLO equity distributions. I believe it’s standard market practice to use the SOFR forward curve to project CLO equity cash flows. This method takes into account anticipated interest rate changes over time. Consequently, CLO equity pricing should already factor in an expectation of declining cash flows.

Targeted CLO equity returns in the mid-teens3 may appear particularly compelling when compared to other asset classes experiencing declining returns. Many investors view CLO equity returns as a premium over the yield offered by CLO BB tranches.

One notable feature of CLO equity is the common practice of incorporating a loan loss reserve into cash flow projections. Given that a typical CLO contains around 200 loans, some levels of defaults are to be expected. For instance, if an investor models a 2% default rate with a 70% recovery rate, any improvement in credit quality — potentially resulting from reduced interest rate burdens on borrowers — could positively impact projected returns.

1 Prequin, Private Equity in 2024, December 2023

2 S&P Global, Default, Transition, and Recovery: 2023 Annual Global Leveraged Loan CLO Default and Rating Transition Study

3 Flat Rock Global estimate using internal modeling assumptions

Lauren Basmadjian, Carlyle’s Global Head of Liquid Credit, joins The CLO Investor podcast to discuss rate cuts, her outlook for CLO spreads, loan default and recoveries, and how she thinks about investing in CLOs managed by other managers.

Like & Subscribe: Amazon Music | Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Shiloh Bates talks to Stephen Anderberg, the sector lead for U.S. CLOs at Standard and Poor’s Global Ratings, about how CLOs are rated, trends in upgrades and downgrades and defaults. They also discuss how the September 18, 2024, interest rate cut may move the market. And they talk about how CLO ratings have performed relative to the more well-known corporate rating system.

Like & Subscribe: Amazon Music | Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Shiloh Bates talks to Ted Goldthorpe, Head of Credit at BC Partners, about the lessons learned in his very impressive financial career. While most asset managers grow their business by launching new funds, Ted is also active in acquiring other asset managers. In this episode, Shiloh and Ted discuss the evolving landscape of private credit and business development companies.

Like & Subscribe: Amazon Music | Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Shiloh Bates speaks with John Timperio, the Co-Head of Dechert’s Global Finance practice, about CLO regulation in this episode of The CLO Investor podcast.

Like & Subscribe: Amazon Music | Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Shiloh:

Hi, I’m Shiloh Bates, and welcome to the CLO Investor podcast. CLO stands for collateralized loan obligations, which are securities backed by pools of leveraged loans. In this podcast, we discuss current news and the CLO industry, and I interview key market players. Today I’m speaking with John Timperio, the co-head of Dechert’s global Finance practice. Dechert is one of the prominent law firms in the CLO industry and someone that I’ve worked with on many transactions with over two decades of experience. John is a trusted advisor to CLO managers and investors. I asked John to come on the podcast to discuss the exciting topic of CLO regulation. This podcast is going into the weeds, so buckle up. If you’re enjoying the podcast, please remember to share like and follow. And now my conversation with John Timperio. So John, welcome to the podcast.

John:

Thank you for inviting me.

Shiloh:

Are you guys having a busy August at Dechert? It seems there’s a lot going on in the market.

John:

We are as busy as I can remember across our finance practice. So I co-head the finance practice at Dechert and we do CLOs. We do ABS, CMBS, and large loan real estate, and all of those silos are going gangbusters. The CLO piece in particular has just been extraordinarily busy, in particular with private credit CLOs, which continue to enjoy or bask in the spotlight of investor demand.

Shiloh:

Gotcha. So how does somebody become a CLO lawyer?

John:

For me, it was a fairly circuitous path. I’ve been doing this for 33 years out of law school. I started doing real estate that market, this was 1991, was dead, transferred into the bankruptcy group, which was going on, firing on all cylinders at that point. When that slowed down after a few years, given my background and understanding of bankruptcy, remoteness and structures, it was a natural segue into structured credit when I started doing structured credit full time in 1998. It was also an interesting period in the market. It was right at the beginning of the CLO world. So I had at that point moved to Charlotte, North Carolina and was doing a lot of work with a bank, First Union, which was highly focused on middle market credit, middle market CLOs, and was able to get in on the ground floor of doing. And those are still

a huge piece of our CLO business 25 years later.

Shiloh:

There’s a lot of CLO lawyers out there. John, how does Dechert differentiate itself?

John:

Great question. There are a lot of CLO lawyers out there, although if you look across the market, there are probably five or six firms that do a bulk of the work. I think what differentiates Dechert is our platform and I think there are a lot of terrific lawyers that can agree to make collateral management agreement, read an indenture, make comments. I think what differentiates us is in addition to the CLO platform, we have the world’s best Advisors Act practice. And if you’re an asset manager, frequently with your CLOs, you have tons of Advisors Act questions or if you’ve got a BDC, you have all these conflicts and other issues that come up. So we’ve got this great platform which includes terrific advisors act practice. Our tax practice is top-notch in the middle market area, really groundbreaking in terms of their views. The tax issues in the private credit space are a lot more challenging for people to get their arms around because you have someone that’s actually originating a loan.

So you have to figure out a strategy if you have an offshore deal or offshore investors. So those can be more challenging. So we’ve got terrific tax practice. So really I think the reason clients hire us is not exclusively for the CLO piece, but it’s all the other pieces. We’re also the world’s leading rated funds practice, CLO equity fund practice, and when clients are putting all those things together, that’s how I think the calculus is tipped in our favor in some cases and it’s been very helpful. So when we’re chatting with clients, it’s focused around the platform and the resources there, and then the fact that we did close to a hundred transactions last year I think gives them a window into the workings of CLOs that can be very helpful as they try to think about what’s market and we can give them up to date, up to the minute color on, well, here’s how this stip or request from an investor is getting settled at this point in time.

Shiloh:

So if I go to a CLO conference today, they always allocate 45 minutes to have some industry lawyers on a panel to talk about what’s new in regulatory issues for CLOs, is there anything that’s top of mind or important for CLO investors or managers today?

John:

Great question. We at the moment are enjoying a relatively, I wouldn’t use the word benign, but stable regulatory front. So good news, is unlike in the years following the financial crisis, the pace of new regulation has slowed. Right now we primarily work with asset managers. A lot of our asset manager clients are focused on some of the conflict of interest rules, which will go into effect in the middle of next year. And their compliance policies with respect to those rules and those rules prohibit material conflicts of interest between managers and sponsors and investors, and were really designed to prohibit transactions that were designed to fail, which was never a real feature of the CLO market. But 12 years later or now finally going to go into effect and managers have to focus on some compliance there and putting up some information barriers. So we’ve been talking to managers about that.

Shiloh:

So John, as you know, CLO securities have performed very well across the stack from equity to AAA on a buy and hold basis from prior to the financial crisis and forward. So what was the push to have… Why was more regulation needed?

John:

Interesting question. I think the answer just based on the hard data is that the industry did not need additional regulation. As you noted, there really weren’t any CLO tranches, there were not many, at least that went into default or didn’t pay in full. So they’ve had a relatively pristine track record in the financial crisis though there was a conflation between CLOs and a product with a very similar acronyms CDOs, which did experience a lot of problems. What’s interesting now, though, is a decade and a half removed from the financial crisis, I do think regulators understand that CLOs are safe products. We have clients who have ETFs that buy CLO liabilities and we see a lot of interest in CLO equity. So I think regulators understand that this is not a dangerous product.

Shiloh:

So the biggest regulatory change for CLOs post the financial crisis was really, in my opinion, risk retention. So maybe you could give our listeners just a quick overview on risk retention, how it worked, and then the remnants of its implementation, how they continue to effect this even today.

John:

So the US risk retention rules are aimed at requiring a securitizer, which is a party that transfers assets into a ABS transaction and asset backed security, to retain skin in the game. And they calculate that a few different ways, but by and large in the CLO space, it’s either with a vertical strip of 5% of the CLO liabilities or an interest in the most residual tranche. The equity tranche equal to 5% of the fair value of all the notes issued in the CLO and initially in the adopting release, the SEC and the regulators took the position that the collateral manager of A CLO was —

Shiloh:

— the securitizer —

John:

— exactly — very controversial position, which resulted in a lawsuit where the LSTA sued the SEC.

Shiloh:

The LSTA is the loan sales and trading organization, that’s the organizational body for the leveraged loan industry.

John:

So they brought suit and the courts ultimately decided that the clear language of the statute was what governed and the language of the statute was based on a transfer of assets into a CLO. The interesting thing is it had two implications. One is open market broadly syndicated CLOs no longer had to comply or did not have to comply with US risk retention. And those transactions, which are the 80% of the market, a manager faces the open

market and purchases either in the primary or secondary pieces of loans into

the CLO from third parties. And basically those deals are designed to allow

these asset management platforms, which are your clients as well. And some of the largest, most well-known asset management platforms in the world to gain AUM and management fees. And the track record is pristine, as you mentioned. The other piece of the market are the private credit middle market balance sheet side of the market that is traditionally or historically always been around 10%.

Last year it was 20%. It’s been hovering in that range as there’s been a lot of buzz and focus on private credit CLOs. That part of the market does have to deal with risk retention because in those transactions you do actually have an originator of assets, generally maybe it’s a BDC or an Alts platform. They actually make the loan, they underwrite it, and then they transfer it into a CLO. They use the CLOs as attractive forms of non-market to market leverage, which frees up other capital for them to make loans. And so in those transactions though, we’ve had to comply with risk retention generally in

those deals, interestingly has not been as big an issue because generally the

platforms that originate the loan want to retain all of the equity, or at least

most of it. I know you all also invest in that equity, but it has not been as

big a problem as it would’ve been on the BSL side where you have these BSL

managers who just could never write the amount of checks that would be required to manage 50 CLOs.

Shiloh:

So then the setup today is basically this. If it’s a broadly syndicated loan CLO, there’s no risk retention in the us. So the manager is not required to buy 5% of the AAA down to equity. They’re not required to own 50% of the equity, which I guess would be the other way to satisfy that previous requirement. And you can do that and you can sell the CLO securities in the US and you’re fine, but for that US broadly syndicated CLO security, if you want to sell it to European investors, then there is risk retention still in place in that continent.

John:

Exactly. What’s been interesting is, as I mentioned, the

middle market CLOs or private credit CLOs, they do comply. There’s some

exceptions, but by and large they comply with US. Sometimes they also comply with European risk retention in order to sell the liabilities to European

credit investors. So sometimes they have dual compliant deals. In the middle

market context, dual compliance is a little more complicated given the type of

reporting that’s required for European compliance. So it’s a little more difficult for them to do that full suite of reporting. But we have a number of clients that have done it and continue to do it. In the broadly syndicated space, even though there’s no US, we frequently have some clients that will set up structures to comply with the European risk retention rules for the same reason it broadens the investor base the liabilities and thereby increases the yield on the equity of their buying equity.

So a lot of what we’ve been doing recently with the managers we set up is set up a structure where they can subsequently use that management company that they’re establishing to hold EU risk retention and thereby satisfy the EU risk retention rules. Interestingly, for BSL CLOs, the reporting is a little easier so that they’re not as troubled, although by that aspect to comply with the European rules, they have to hold 5%. Europe measures it a little differently. They look at 5% of the notional of the portfolio. So it’s a slightly different calculation than the US, but gets you roughly in the same ballpark. So if you think about the market or the landscape private credit, by and large, you do have transfer orders and they do comply broadly syndicated, no US risk retention. They sometimes comply with European in order to facilitate better execution. What’s interesting is there’s another part of the market that’s really picked up steam and that relates to rated feeders, rated note funds, and those are really primarily or exclusively in the private credit space, but they’re initially started out as feeders into private credit funds where people were structuring a feeder so that it had rated debt to facilitate investment by insurance companies.

But now sometimes those deals are very similar to CLOs and the tranching and how they look. But what’s interesting about that market is by and large, because there’s still a lot of fun like aspects to those transactions, people have not treated those as needing to comply with US risk retention. So you do have this other category, and that’s a very burgeoning part of the market on the private credit side.

Shiloh:

Why was it that risk retention was in the US only repealed for broadly syndicated CLOs and not for middle market CLOs?

John:

It was really because the way Congress had drafted the statute was to require a securitizer to hold risk retention, and they define securitizer as the party that organizes and initiates the transaction by transferring assets into the CLO. In a middle market context, you do actually have originators that transfer much like ABS deals. In the broadly syndicated CLO market, the asset managers just acquire from third parties in the open market, much like stock picker of a mutual fund would acquire stocks.

Shiloh:

So though in middle market CLOs, even though risk retention exists, what I see is that the manager of the CLO, they want to own securities in the CLO as well. So they’re required to do it by law, but they want to own a majority of the equity. They often take strips of the senior securities. So it’s not really a burden for them. At least that’s my perception of their business model.

John:

Absolutely. I think what’s been interesting to me, well a few things. One is over the last, I’d say again, 24 months or so, we’ve seen much greater interest in CLO equity and had a bunch of clients raise CLO equity funds. I think that that on the broadly syndicated side, not on middle market, so a number of BSL managers have gone out, dedicated CLO equity funds, and used that money to invest into their own CLOs generally in a way that was EU compliant as well. And that has been something that’s interesting because if you go back five years ago, those who are very episodic, where we might do one or two a year, now, we probably have 10 going on at the moment, people are able

to raise that money. We don’t see that in the middle market space for the

reason you mentioned, the managers really don’t always want to part with that equity and really when they are, they’re going to do it with a strategic

counterparty like a Flat Rock, who they trust and they know they’re going to be a good actor in our transaction.

Shiloh:

So then is there any expected changes to the risk retention framework that exists today? Are there any proposals out there to do it differently?

John:

No expected changes. Certainly there could always be new rule-makings, but nothing we’re aware of in the pipeline. What’s interesting is some of the vehicles that we helped set up in the very early days when people thought it was going to be applicable to both BSL and middle market are still around and in some cases highly successful. The one that comes to mind is Redding

Ridge, which is 25 billion or more in AUM at the moment.

Disclosure:

Note Redding Ridge Asset Management is an independently managed affiliate of Apollo specializing in structured credit.

John:

And that was set up initially as a collateralized manager vehicle, which was an option where you set up an independent company from the main platform and raise capital into that. And that vehicle has been incredibly successful and like I said, still exists and has an AUM that’s very enviable.

Shiloh:

So I guess the punchline is risk retention has gone away, but the manager in the past was able to raise risk retention funds and presumably the funds performed well. So even though the requirement isn’t there today, they keep these funds active.

So then changing topics, I know you guys work on negotiating both middle market and broadly syndicated CLOs. What are some of the key legal differences between the two?

John:

Very interesting, and we were involved with the full evolution of the private credit market and initially those deals emanated out of an ABS-type structure where it was repurchase and all this recourse back to the originator or the assets.

Shiloh:

So an asset backed security, so different from a CLO or what’s the terminology there?

John:

It would be asset backed security. So —

Shiloh:

— securitization of business equipment or aircraft —

John:

— that was the original DNA of middle market CLOs. And then over time they did converge and now the technology is largely the same, but they have a number of characteristics that are different between the two. And first off, the motivations are vastly different. As I mentioned, middle market CLO managers largely use the CLO as just a financing source for collateral, whereas in the broadly syndicated space, they’re really using these as a way of gaining AUM management fees, and as arbitrage vehicles. High level differences as you look at the two first, the collateral obviously middle market CLOs, the collateral is less liquid; generally has credit estimates versus public ratings, and there’ve been the B minus range, whereas the BSL broadly syndicated loan space, it’s a little higher, maybe B/BB minus. Generally middle market CLOs, the loans and middle market CLOs generally have covenants, which in our BSL world is not always the case and most of the collateral will not have covenants.

It’ll be covenant light as we say. Another difference is because the collateral is a little lower rated to begin with, there generally tends to be a higher triple C bucket and middle market CLOs than broadly syndicated CLOs. So generally 17.5% or slightly more in a middle market CLO, whereas in a broadly syndicated CLO, you might have 7.5% and then other differences, there’s a lot less trading that goes on in middle market CLOs, again, both the collateral and liabilities or much less liquid. And this generally with middle market CLOs and there’s lots of exceptions to each of these, but there’s generally not reinvestment, post reinvestment period. So again, the weighted average life will vary from a broadly syndicated CLO. The other thing I’d mentioned, and this would be attractive for investors, is there’s more credit enhancement at all the levels of the tranching. The equity is generally a larger piece of the overall transaction in a private credit middle market CLO than a BSL CLO. So the structures are sturdier than a BSL CLO, which are also have performed in a terrific way. So not to cast dispersions there.

Shiloh:

So I think one of the things that is newer in CLO documentation today is the ability to protect yourself in a scenario where the underlying loan is being restructured. So the typical CLO would prevent the CLO manager from buying an equity security for example, or participating in inter-rights offering or maybe even buying a debt security that’s currently in default. Those are things that would generally, you think of them as being prohibited. In the past, distress funds would buy up loans of underperforming companies and

they would propose, through the bankruptcy process, a restructuring where a lot of the residual value of the company would come back in equity or warrants or other securities that the CLO couldn’t purchase. And one distressed manager described their business as arbitraging CLOs in this manner. So they buy the discounted loans, they propose an all-equity restructuring, that would result in CLO managers dumping even more of the loan to their advantage. And a distressed fund probably has no issue in buying equity and restructured companies. So the distressed funds were really taking advantage of the CLO’s strict rules, and over the last few years, there’s been a real effort to true that up so that CLOs can play on an equal footing in a restructuring process.

John:

Look, that was an interesting moment where as you pointed out, you had distressed and investors realizing that CLOs were limited in what they could purchase and really trying to take advantage of that. As you note though, over the last couple of years, by, I would say consensus of the market, really all the investors, those limitations or prohibitions or risks to CLO investors have been largely mitigated primarily through allowing the CLOs to purchase workout loans, which may include some securities as part of the package. Additionally, CLOs do now have, because of changes in the Volker rules, an ability to buy permitted loan assets, which had historically been a problem prior to the changes in Volker, there was a restriction where CLOs could not buy securities, equity securities, unless they were received in part of a restructuring, and that created a lot of risk for the CLOs.

Now they can actually own permitted non loan assets. So you’ve got a confluence of things along with an ability to contribute money for permitted uses, which includes buying workout loans and equity securities, that really have closed out loophole. But it was an interesting moment because you

saw these creative distressed fund managers all realizing that there was this

problem, and CLOs obviously own two thirds of the leveraged loan market, and it was very frustrating time for our clients. A number of those older CLOs were amended, and now the new deals do have a bunch of mechanics to address that.

Shiloh:

Well, one of the, I think easiest, mechanics is just that if the CLO manager wants to buy workout loans or other loans, that would generally be prohibited. The solution is you can buy them, but you just need to use cashflow that would’ve otherwise gone to the equity. So that’s a win-win

for everybody because the equity wants to make that investment because it’ll

improve the loan recoveries and that benefits the debt investors in the stack

and doesn’t come out of their pocket. So I think that’s one workable solution

there for everybody.

John:

Absolutely. And we see that uniformly with these

supplemental reserve accounts, which are prior to the distributions to equity.

People having an ability to put money in there and use it to fund workout loans and the like. So I agree with you, very helpful. The other thing you see is, now with permitted uses and contributions, equity can also make a contribution. So it’d be on a date other than a payment date to acquire the equity securities.

Shiloh:

So then when indentures are coming together today, what do you see as top few negotiated items, items where maybe the AAA and the equity have different views, or maybe the manager and some of the investors have

different views? What are you seeing being highly negotiated in docs?

John:

It obviously varies a bit from the perspective of who’s making the request. A lot of times the AAA investors are going to be focused around consent rights to lots of different things in the documentation. There’ll be a lot of negotiation around when you have to go get controlling class consent. They may also be focused a little bit around some of the concentrations and some of the buckets. So it varies a bit. I think what’s been interesting is recently with the changes in Basel III and improved regulatory capital treatment at the AAA level where they reduced it from 20% to 15, we’re now seeing greater interest amongst bank investors. And that’s been interesting and

driven a lot of changes with loan classes and the like, and certainly been a

positive change for the market to have the banks come back at the AAA level.

The other thing we’re seeing a lot of focus on, at least at the moment, is it

seems like people are very, I wouldn’t say concerned, but focus on PIKing

assets and the treatment of PIK assets and how they impact various tests like

the overcollateralization tests. And if you have a PIKing asset that is paying

a certain coupon, making sure that that is not haircut for OC tests. So it

seems like a lot of clients the moment are a little bit nervous around assets

that may defer some interest.

Shiloh:

So a PIK loan is one in which the loan is not paying interest or partially not paying interest. So the interest that would’ve been paid is capitalized into the par balance of the loan, which is growing over time. So I guess the question there is for the purposes of the par tests or the OC tests, higher PIKed balance of the loan, or is it the initial balance of the loan? That’s what we use in that ratio, is that correct?

John:

Absolutely.

Shiloh:

So I guess the reason that it’s maybe a negotiated point. On the one hand, why wouldn’t you use the current par balance of the loan? That would make a lot of sense. On the other hand, the loan is PIK presumably because the borrower doesn’t have the capacity to pay in cash. So it’s probably a principal balance of a loan that might be more at risk than a different loan that’s just making its contractual interest and principal payments each quarter.

John:

That’s right. Another thing I think we’ve seen more of this year, or at least recently has been truly private credit CLOs. So private credit CLOs where there’s no offering circular, just a handful of investors negotiating with a manager originator. And that’s been interesting. Again, it just shows the interest level and a lot of times you have insurers buying the rated liabilities there, so there’s been an uptick of those types of transactions as well.

Shiloh:

Is there anything else interesting happening in the CLO world today?

John:

I would say the one other thing that’s been really fascinating, I mentioned all the creativity in the rated fund rated feeder space, that space not exist five years ago. And since then there have hundreds of transactions in that space, and I think we have 30 going on in some fashion at the moment at Dechert. So red hot space. Also an area where a lot of creativity going on the box is not as narrow because you’re not solving for CLO ratings methodology. They use closed end fund methodology and lower tranche attachment points. So there’s a lot of flexibility there. But the other area that has been interesting to me has been the growth of joint ventures. This is again on the private credit side, joint ventures between middle market originators, managers,

and banks. And again, if I look at it historically, I’d say, well, we had

historically done maybe one a year, one every two years.

Now we’ve seen, and you’ve seen in the press, a number announced of these joint ventures where basically you have banks who will originate private credit loans and source them to middle market originators. Sometimes the bank JV Partners will also provide back leverage to the private credit manager on that portfolio. Sometimes they set up a private credit vehicle jointly and invest into it. So there are all these different permutations there, but that area has been proliferating. And it’s an interesting thing too because if you look at what is the proper role of banks, banks have trouble holding lots of leverage loans in their balance sheet, but they can be great syndicators of credit and earn very rich sourcing fees in that process. So you have the banks dealing with this long-term secular issue of they can’t hold leveraged loans, and for the first time being creative and saying, well, we may not be able to hold them, but we can source them and earn these fees. And then you have these private credit managers who are able to utilize the boots on the ground that these banks have. So it’s a win-win situation, and that’ll be interesting as those loans eventually make their way into CLOs, but that’s been a development that is quite novel.

Shiloh:

Interesting. John, thanks for coming on the podcast. Really enjoyed our conversation.

John:

Absolutely, and thank you for inviting me.

Disclosure:

The content here is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as legal, business, tax, or investment advice or be used to evaluate any investment or security. This podcast is not directed at any investment or potential investors in any Flat Rock Global Fund.

Definition Section

AUM refers to assets under management.

LMT or liability management transactions are an out of

court modification of a company’s debt.

Layering refers to placing additional debt with a priority

above the first lien term loan.

The secured overnight financing rate, SOFR, is a broad

measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight, collateralized by Treasury

securities.

The global financial crisis, GFC, was a period of extreme

stress in global financial markets and banking systems between mid-2007 and

early 2009.

Credit ratings are opinions about credit risk for long-term issues or instruments. The ratings lie on a spectrum ranging from the highest credit quality on one end to default or junk on the other. A AAA is the highest credit quality. A C or D, depending on the agency issuing the rating, is the lowest, or junk, quality.

Leveraged loans are corporate loans to companies that are not rated investment grade.

Broadly syndicated loans are underwritten by banks, rated by nationally recognized statistical ratings organizations and often traded by

market participants.

Middle market loans are usually underwritten by several lenders with the intention of holding the investment through its maturity.

Spread is the percentage difference in current yields ofvarious classes of fixed income securities versus Treasury bonds or another

benchmark bond measure.

A reset is a refinancing and extension of a CLO investment

period.

EBITDA is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization. An add back would attempt to adjust EBITDA for non-recurring items.

ETFs are exchange traded funds.

CMBS are commercial mortgage backed securities.

A BDC is a business development company.

Basel III is a regulatory framework for banks.

The source for middle market CLO issuance percent is JP Morgan CLO research.

General Disclaimer Section

References to interest rate moves are based on Bloomberg data. Any mentions of specific companies are for reference purposes only and are not meant to describe the investment merit of or potential or actual portfolio changes related to securities of those companies unless otherwise noted.

All discussions are based on US markets and US monetary and fiscal policies. Market forecasts and projections are based on current market conditions and are subject to change without notice. Projections should not be considered a guarantee. The views and opinions expressed by the Flat Rock Global speaker are those of the speaker as of the date of the broadcast and do not necessarily represent the views of the firm as a whole.

Any such views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions, and Flat Rock Global disclaims any responsibility to update such views. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, or investment advice. It is not a recommendation, offer, or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. Neither Flat Rock

Global nor the Flat Rock Global speaker can be responsible for any direct or

incidental loss incurred by applying any of the information offered. None of

the information provided should be regarded as a suggestion to engage in or

refrain from any investment-related course of action as neither Flat Rock

Global nor its affiliates are undertaking to provide impartial investment

advice, act as an impartial advisor, or give advice in a fiduciary capacity.

Additional information about this podcast along with an edited transcript may

be obtained by visiting flatrockglobal.com.

Allan Schmitt, Head CLO Banker at Wells Fargo, joins Shiloh Bates for this episode of The CLO Investor. Allan and Shiloh talk about rated feeders, a new flavor of CLO (collateralized loan obligation) that is growing in popularity.

Like & Subscribe: Amazon Music | Apple Podcasts | Spotify

Shiloh:

Hi,

I’m Shiloh Bates and welcome to the CLO Investor podcast. CLO stands for

collateralized loan obligations, which are securities backed by pools of

leveraged loans. In this podcast, we discuss current news in the CLO industry,

and I interview key market players. Today I’m speaking with Allan Schmitt, the Head CLO Banker at Wells Fargo. Allan has structured many of the CLOs I’ve invested in, and at my prior firm, Allan was part of the team that provided our business development company, an asset-based lending facility, or ABL, and ABL is just leveraged against a pool of leveraged loans. As you’ll hear during the podcast, Wells is active both in lending against diversified portfolios of loans and arranging their securitizations through the CLO market. I asked Allan to come on the podcast to discuss rated feeders, which are a new flavor of CLO that is growing in popularity. If you’re enjoying the podcast, please remember to Share, Like, and Follow. And now my conversation with Allan Schmidt. Allan, welcome to the podcast.

Allan:

Thanks, Shiloh. Excited to be here.

Shiloh:

Is it a pretty slow August on the CLO banking desk?

Allan:

I think most people might wish it was, but it’s definitely

been an interesting summer across the board. I think we’ve seen, obviously with

CLO spreads tightening, really across the balance of the year, has created

really an overwhelming number of reset and refinance transactions for the

market. So not only Wells, but across the board, you’re seeing 10, 15 deals a

week come across the transom. So I think everywhere from the investor side, as

I’m sure you’re aware, to the underwriter side, to the manager side, to the

lawyers, the rating agencies, I think everyone is really working through the

screws to get transactions through the pipelines here in August. So…

Shiloh:

It definitely seems that way. We’ve known each other for

quite some time. And maybe you could tell our listeners a little bit about your

background and how somebody becomes a CLO banker.

Allan:

Sure. So I’ve fortunately been in the industry around CLOs

my entire career, which dates back to 2006. So started right before the global

financial crisis. Certainly as an analyst at that time, it was an interesting

period to really begin to get involved in the market and certainly had a front

row seat to a lot of the activity that was happening at that time. My entire

career has been with Wells and predecessor firms, so I’ve been fortunate from

that perspective and as we moved out of the global financial crisis, was able

to be really on the front lines as well as we built the business at Wells

around private credit lending, around CLOs, and really was instrumental in

terms of growing my knowledge base, growing both internal and external

relationships during that period. So obviously where I sit today in my current

role, lead both our CLO effort across both broadly syndicated and middle market

CLOs as well as our private credit lending business there. And as we’ll talk

about more recently expanded our offering underrated feeders as just an adjunct

to what we’re able to do for our private credit clients. So obviously a

longstanding period of time here in CLOs, but excited about it.

Shiloh:

So what are some of the key character traits of somebody

who’s successful in CLO banking?

Allan:

So I think it’s a number of things. I think first and

foremost it’s being a relationship manager, so someone that’s communicative

both to internal counterparties, but even more importantly to clients and

investors like yourself, folks that have the ability to think dynamically on

their feet. CLOs are not an overly complex structure, but they do require the

ability to put pieces together both from a structure perspective but also the

different constituents, both equity manager investors. And so being able to

play that process effectively and walk out of transactions where everybody

feels it was successful I think is a key piece. So someone who can manage that

process and communicate effectively is critical and certainly is depending on

where we’re hiring people as folks move up the ladder, really being able to

develop and institutionalize a lot of the client relationships that we have in

the market.

Shiloh:

And then for the junior people you hire, are they spending

a lot of their time doing financial models? So accuracy is the key

differentiator there?

Allan:

Yeah, I think attention to detail, right, to your point,

and being able to both be intellectual around structure, documentation, et

cetera is obviously critical. Obviously it’s a learning curve that folks have

and folks get into, but someone that has that ability to grasp both the legal

and structural aspects of the business quickly, and obviously having that

strong attention to detail, is obviously important as well.

Shiloh:

And so as you become more senior in the CLO business, is

somebody like you still in the weeds with the modeling or are you reviewing at

a high level the work that’s done by others?

Allan:

I spend a lot of my time, I think on the client

development side of things, the more strategic side, whether that’s when we’re

bringing a CLO transaction, helping to formulate the distribution process, the

distribution strategy, certainly on the structuring side as well, helping to

provide ideas and thoughts around different structural nuances or things we can

focus on within specific transactions. So while not in the weeds punching

numbers necessarily, certainly maintaining a pulse on what’s happening in the

market and how we can create better structures for our clients to optimize from

an ultimate execution perspective.

Shiloh:

So I think there’s around 15 or so different CLO banks out

there. How is Wells differentiated from some of the others?

Allan:

There’s certainly a lot of players in the market around

syndicated CLOs and even becoming more around middle market CLOs. I think from

our seat, we try to differentiate ourselves a couple ways. One, I alluded to

the bAllance sheet that Wells provides into the private credit space, and I

think that has an extension into the broad syndicated market as well. And it’s

not just about providing bAllance sheet, but it’s providing that capital in a

way that is beneficial to client and can help drive business for the platform

holistically. But it’s also around providing bAllance sheet on a consistent

basis. I think what I mean by that is our approach to lending over the course

of the last 15 to 20 years has not changed materially. I think we’ve always

been an active participant or a leading participant in the private credit

space. So our clients have confidence, have an understanding in terms of how we

approach the market.

So that consistency, we obviously want to adapt and evolve

as the market evolves, but our ability to maintain consistency across different

markets, whether it’s volatility, as we saw earlier this week or what have you,

we’re able to consistently provide that capital to clients both in a strategic

and customizable way. I think the other is, it sounds simple, but from a

customer service perspective, the relationship management perspective, our

ability to help clients on the financing side for a lot of their funds from

start to finish is critically important. When we think about a lot of the funds

that have been raised, they need multiple forms of financing, whether that’s

traditional ABL financing, CLO financing.

Shiloh:

An ABL is an asset backed loan.

Allan:

That’s right. Wells is providing the senior financing on a

pool of loans, so substituting a CLO, AAA, AA for a bank, ABL financing.

Shiloh:

So there the point you’re making is that Wells actually

likes to lend against these loans, so you’re going to require some third party

equity obviously, but maybe before there’s ACL O, there’s a warehouse set up

where somebody again puts up some equity and wells starts advancing the debt

there and maybe there’s a CLO takeout at some point or maybe there’s not. And

either way, Wells likes to take the senior risk, if you will, against a pool of

senior secured loans. Is that how to think about it?

Allan:

That’s exactly right. When we think about our client base,

a lot of the financing to private credit is not necessarily in CLOs, it’s in

that ABL structure or that bank financing structure. And so we’re able, and we

like that product, we like that lending, its core to what we do as a business

and a platform. So we’re able to provide that to clients, but we’re also able

to facilitate and think about strategically the execution of CLOs for clients

as well. So all of that from a relationship management perspective, all of that

sits within our team. So we have the ability to really provide clients with

ideas and thoughts around the best form of financing for their funds.

Shiloh:

At a previous firm, as you know, I was the counterparty to

a Wells line of credit where Wells was lending against a diversified portfolio

of middle market loans, and I think generally an advance rate of 65 or 70%. Do

you have any sense for why it is that that business works for a bank like Wells

and other firms may not find that business to be as appealing?

Allan:

I think it’s interesting. I think we’ve seen other

institutions I’d say come around or become more active and engaged in that

senior lending there. So I think when your question on how does Wells

differentiate, we differentiate because we have consistency and a long-term

process around that business. But I think other banks and institutions are

active in it, are growing in it, and it’s becoming a more competitive space

there.

Shiloh:

So one of the things I’ve noticed in the CLO equity trade

is that before the CLO begins its life, often there’s this warehouse period

where some equity is contributed and loans are acquired using leverage from a

bank and at other banks, that warehouse is really something they’re providing,

really they want it to be as short as possible. They don’t really like the

risk, they want you to be in a warehouse for a couple months, then they’re

ready to do a CLO and then they earn a fee, the bank does. And then there’s no

real exposure to the CLO after that. In some of the warehouses I’ve done with

you guys in the past, the vibe is you put up equity, Wells like lending against

the loans as a senior lender, and we can do a CLO takeout soon or later or

maybe never. And it seems you guys are fine with that, which I think is

different from some of the other shops.

Allan:

I think it certainly obviously depends on the situation

and the structure of the motivation, if you will, of that vehicle at the

outset. But to your point, we are able to be patient. Again, we approach it

very much from a client relationship type perspective and want to find the best

takeout and the best long-term structure for the client. I think we certainly

want to do CLOs, we certainly want to earn fees on the backend, but in certain

structures we’re not here to force the takeout and want to develop partnerships

for the long-term. And I think we’ve done that over the years and you can see

that obviously in some of the repeat managers that we partner with, but

definitely take a longer term view of that warehouse to take out than some

others.

Shiloh:

So then in the CLO market, the three biggest categories

for CLOs would be European versus US, and then, in the US, and by the way, we

don’t do anything in Europe. And then domestically it’s broadly syndicated CLOs

and middle market are the big two. Could you maybe just compare and contrast a

little bit the structural differences between the two and then from there maybe

we could build into the rated feeders as well?

Allan:

Definitely, and I think when you think about those two

markets, probably syndicated and middle market CLOs, at this point, there’s not

a lot of structural differences between them. You certainly have similar rated

notes, you have similar reinvestment periods. BSL might be five years, middle

market might be four years, albeit there are middle market CLOs now getting

done with five years. I think the bigger difference really when you think about

the two markets is the underlying motivations for transactions. So middle

market CLOs are used typically by managers in most senses as financing vehicles

for larger fund complexes. We talked about the ABL business that Wells does and

others do, which is a big form of financing for these larger fund structures.

And CLOs are another form of financing. So where broadly syndicated CLOs are

going to be much more of a true arbitrage structure, where the manager is

partnering with equity and are going out and buying loans in the secondary

market, buying loans in the primary market from large institutional banks. The

middle market is much more of a longer term financing vehicle where they’re

originating assets on a direct basis over a long period of time and turning

those assets out. So the motivation that you see between the two is probably

the biggest difference there.

Shiloh:

So in your terminology, an arbitrage CLO is one where

there’s a third party equity investor who’s signing up, likes the risk return

profile of the investment, and that’s who the end investor is there. And then

for middle market, a lot of times it’s a financing trade. So by that there may

be a BDC or a GPLP fund with a diversified portfolio of loans and it’s

advantageous to them to seek leverage against that because it’s long-term

leverage done at attractive rates and that enables the BDC or GPLP fund to increase

their return on equity. But in a structure like that, the equity is owned a

hundred percent by the BDC or the fund. There’s no third party equity, there’s

no Flat Rocks involved in that case.

Allan:

That’s right, and I think that’s also when you think about

one of the bigger differences between the two BSL and middle market CLOs, BSL

is typically always going to issue down through double B rated notes or all the

way through equity and middle market Cs because of that financing structure for

BDC or a fund, they may only issue down through AA or single A because the

leverage profile of those vehicles or how much leverage those vehicles are able

to run is meaningfully less. So that’s why a lot of times you won’t see

mezzanine or non-investment grade tranches issued for middle market CLOs.

Shiloh:

So the broadly syndicated CLO might be levered, was it 10

times on average, where the middle market might be leveraged seven and a half

times. So less leverage there. And then the CCC basket is another big

differentiator. In broadly syndicated, you get a seven a half percent triple

CCC bucket. In middle market, you get 17 point a half on average. Of course

there are some differences in deals and that gives the manager more flexibility

because the middle market loans tend to not be as favorably rated by Moody’s or

S & P. And then you pointed out the middle market CLO might have a four

year reinvestment period, so a little shorter than the five years you get in

broadly syndicated. I think those are the key differences. Another minor one

would just be reinvesting after the reinvestment period ends. So in broadly

syndicated CLOs, whenever you get unscheduled principal proceeds, whenever

those come back to you, which is most loan repayments are unscheduled anyways,

then a lot of times you can reinvest that, subject to some constraints in the

deals. Whereas for middle market, actually the reinvestment period ends. It’s

very simple. There’s no more reinvesting. It sounds like a subtle difference,

but I think it does actually matter in terms of how long the deal will be

outstanding for and it matters for equity returns. I think. If you think about

the aaa, which is the biggest financing cost and broadly syndicated, the loan

to value through AAA is going to be about 65% would you say, or

Allan:

62 to 65%

Shiloh:

62 to 65. And then for middle market it’s going to be

Allan:

55 to 58.

Shiloh:

So it sounds like you get a lot more equity or juniorcapital in the middle market. And then in terms of your banking team, you havea middle market team and a broadly syndicated team, or these are similarproducts and everybody works on the different deals?

Allan:

As we’ve talked about, there’s similar enough products where we generically have everybody working on similar deals. We do have some senior members of the team more from a relationship perspective that are specialized in either BSL or middle market as they think about developing client relationships and whatnot. But from a structuring deal execution

perspective, we view there to be enough similarities between the products and certainly from an investor perspective as we think about distribution of the products, that there’s enough similarity where the same individuals are able to function there.

Shiloh:

And then one of the reasons I wanted to have you on the podcast this week was just to talk about rated feeders a little bit. So that’s a new flavor of CLO in the market. What are the basics of a rated feeder?

Allan:

So a rated feeder is a structured credit vehicle where, as opposed to being secured by underlying assets directly, as a CLO would, you’re secured by the LP interest of a private credit fund. And that private credit fund can really be of any type. It can be direct lending, it can be asset-based lending. It can be all sorts of different types of private credit assets, but for the most part, most of them have been done off of middle market direct lending assets. The structure has been utilized for many years. As you think about insurance companies who want to make investments in private credit funds, they’re able to do so through a rated feeder structure in a more capital-efficient way. So again, the underlying asset that is getting levered or is getting tranched out is an LP interest of a private credit fund. So when you think about that GPLP structure, LP fund where you have multiple different institutional investors making LP commitments, some of them might be insurance companies that want to gain access to that fund.

So for them to do that through a rated feeder structure, they’re able to do so in a more capital efficient way. And the reason for that is the leverage profile of a lot of these funds, as we talked about earlier, is only one or two times leverage. So they’re run at fairly low leverage points. And so while the rating agencies are able to get comfortable by tranching out that LP interest and adding incremental rating levels to that for any investor, but predominantly insurance companies to receive incremental capital efficiency there. So historically to this point or to recently, insurance companies have bought vertical strips as we call them, buying a AA, single A, triple B in equity of that rated feeder. And so they’re buying the entire portion for that capital efficiency. But most recently we’ve really thought about that structure on a more horizontal basis, which is more akin to middle market CLOs where we’re using that same radium methodology that insurance have used in trying that out, but selling that to different investors at different risk return profiles there. So instead of one investor buying it all, we might be selling AA, single A to different investors.

Shiloh:

So I think the structural setup here is, imagine your rated feeder, let’s call it 300 million, and let’s say the underlying fund is BDC just to make it simple. Then the rated feeder takes the 300 million that it raises from third parties, it injects that into the BDC, and the BDC over time will pay dividends up to the rated feeder in the dividends on the 300 million that arrived at the BDC. But in the rated feeder structure, as those dividends get passed up to their rated feeder, instead of having all the dividends just paid out rata to the 300 million of equity, instead the setup is the tranching that you mentioned, where first there’s a AAA or AA or whatever it is, they have the first priority on the dividends from the BDC down the line, and then there’s an equity investor and the rated feeder as well, and they’re the person who gets paid whatever remains.

So again, the total income into the rated feeder is the distribution from the BDC, and it just split up, senior to junior, with equity taking the remainder. One of the reasons these exist, I think to your point, is that if you’re an insurance company, you’re basically investing 300 million into the BDC. So the insurance company can either end up with a $300 million limited partnership agreement or LP investment in a BDC, or they can end up with 300 million of investments in a series of securities rated AAA or AA, whatever it is down the line to double B, and they’ll get just much more favorable regulatory treatment for that. So if you’re an insurance company, you don’t want to own a lot of equity, you want to own as many senior rated securities as you can.

Allan:

That’s exactly right. When you think about the rated feeder, especially to your point on the waterfall and how cash is distributed, it doesn’t look that dissimilar than any other structured vehicle where cash is being distributed down through the priority of payments or through the different ratings to the equity at the bottom. I think the difference obviously is there’s effectively one asset. So one LP interest to the fund is distributing that cash into the vehicle that’s getting distributed versus a CLO that might have a hundred unique assets where the cash is coming in. So the investors are really one step removed from the assets than they would be in a middle market CLO. But you have as an lp, as the rated feeder acts as an individual LP of the fund, it has the same rights that any other LP would have in terms of access to the assets.

Shiloh:

So then I understand the rationale for why an insurance company would want to use this structure, but are you also seeing interest from other investors that don’t have regulatory capital that would care about a Moody’s or an S & P rating?

Allan:

Certainly. So obviously the insurance company has been the predominant of the product there, but we have seen an expansion of that beyond insurance companies, not so much as to where they’re focused on capital charge

treatment, but investors are more focused on where they can find increased

spread or increased return really within the same asset class. So the ability

for banks or asset managers or hedge funds or different CLO investors, the

ability for them to buy a more structured complex vehicle is going to come with it a higher spread or a higher return. So we have seen a lot of investors,

we’ve seen spread compression across markets, look at rated feeder notes and look at these structures as another way to really gain access to the asset

class where there’s the ability to garner incremental spread through that level

of complexity through that level of illiquidity there. So we’ve obviously done

a few of these to date and have probably seen the investor base on each

subsequent one continue to grow and broaden and are seeing broad interests and growth there.

Shiloh:

So the most senior securities that are issued by the rated feeder, are they actually rated AAA or is it more of AA, single A, because you are, as you said, one step removed from the assets?

Allan:

So the most senior tranche in rated feeders is really AA. Most of them are either that single A or AA is the most senior rating. It’s certainly because of the one step removed from the assets. The other piece is the fund that sits above the rated feeder is also running leverage. So there’s leverage at that fund level, usually in the form of a bank ABL as we talked about. It could be in the form of CLO tranche, it could be in some other unsecured debt tranche, but there is some form of leverage typically at the fund level that sits above the rated feeder. So that’s another reason why obviously, from a rated entity perspective, they factor that fund level leverage into the rating as well.

Shiloh:

So then let’s just compare for a second, owning the AA of middle market CLO versus the AA of the rated feeder. So in the rated feeder, you do have this ABL sitting at the fund or the BDC level that has first priority or that’s in the first security position. If you’re sitting at the rated feeder, all the management fees and incentive fees that are paid to the manager of the BDC, those are taken out before any distributions are sent up to the rated feeder. So essentially those become senior to you even if you’re AA, whereas in the typical middle market aa, the only expenses you have ahead of you would be AAA interest and a senior management fee. Maybe there’s a little bit of other operating expenses, but it wouldn’t be material. So that rated feeder AA is removed from the assets, has an ABL in front of it, but also the management and incentive fees of the fund take priority as well.

Allan:

That’s exactly right. I think the biggest difference there though is the attachment or the leverage point of the ABL of that senior debt to the rated feeder. So to our earlier conversation on comparing middle market CLOs, when you look at the attachment of a AAA on the middle market, CLO, that’s all the way down to 55 to 58% advance rate. A lot of the rated feeders, certainly on the AA side that are being issued, the senior debt or the ABL is

only the 40 to 50% attachment. So you’re adding incremental subordination

through that senior ABL to the rated feeder to make up or offset some of those incremental expenses and fees that you alluded to.

Shiloh:

So I elicit the cons of the rated feed feeder AA, but the amount of junior capital that supports that is much higher than in the CLO. At the end of the day, they’re both rated AA, so presumably they would’ve the same credit quality.

Allan:

That’s the idea. And I think there’s obviously going to be pros and cons of each, but I think to your point, one of the biggest pros is the added subordination that exists for the rated feeder notes. In comparison to middle market CLOs.

Shiloh:

Let’s maybe just also compare owning middle market equity directly versus owning it in the rated feeder. What are some of the key structural differences there?

Allan:

So I think some of the key differences when you think about rated feeders to middle market CLOs is I like to think about rated feeders, really, they combine both the warehouse period for a middle market CLO and the term securitization. So when you think about a middle market CLO, as we

talked about, there’s a warehouse period that exists that equity has to come

into, the manager has to originate assets and you’re ramping assets over an

extended period of time, and then ultimately waiting for the securitization or

the long-term financing structure of that pool of loans or what’s the most

optimal time to do that. On the rated feeder side, it really combines both of

that warehouse structure as well as the term structure into one. And it does

that obviously through the fact that the notes are issued in delayed draw form. So the senior notes integrated feeder are typically done in delayed draw

fashion. So that allows the portfolio of the fund to be ramped up on a consistent basis, but also being able to draw that leverage as assets are contributed, whereas a middle market CLO is going to be fully funded or fully drawn day one. So that’s I think one of the bigger difference. The other is when you think about middle market assets, there’s a large delayed draw and revolver component that comes alongside those assets, whether those are being contributed to the fund or a middle market CLO, the manager has to find solutions for those. And in a middle market CLO, you’ll typically find

portfolios anywhere from five to 10% in delayed draws and revolvers, and that’s a drag to equity at the end of the day. In terms of having to cash

collateralize a portion of those assets in the vehicle. With the rated feeder,

you’re going to have a similar delayed draw and revolver component to the

portfolios. But the ABL line, the bank ABL line that we’ve talked about

functions as a revolver, so it’s more of an optimal solution to fund those

assets. So there’s going to be less negative drag or less negative carry on the

fund and ultimately the rate of feeder than there would be in a middle market

CLO.

Shiloh:

One other structural difference that we haven’t really talked about is just that in the middle market CLO, it’s almost exclusively firstly in senior secured loans. So the spreads are going to vary a little bit, but it’s three months sofa plus five to five and three quarters on the high end, whereas in the rated feeder, the underlying BDC or fund might be something more like 85% first lien, and then there’ll be a fair amount of second lien or pref or some other funky stuff there. The asset pools do look a little bit different.

Allan:

For sure, the rated feeder depending on the fund, but most of the funds that are utilizing the structure, there’s a lot more asset flexibility associated with it. So there’s the ability not only at the outset, at the original ramp, to be opportunistic in certain maybe non-first lien assets or recurring revenue, which are a big part of a lot of direct lenders. Today is obviously a key differential where middle market CLOs you’re required to be 95% first lien highly diversified. You have obviously collateral quality tests or other items that the managers have to manage too. So there is a lot more asset flexibility that’s allowable in rated feeders, and I think that’s at the outset, but also as the portfolio evolves and as there’s market dislocation, managers have slightly more ability to take advantage of that asset flexibility over time.

Shiloh:

So then moving back to we were comparing and contrasting

the middle market AA and the rated feeder AA, which should offer a higher

return, in your opinion?

Allan:

The rated feeder AA should offer more return to the investors for a couple of reasons. One, there is more structural complexity associated with it, and that’s in the form of obviously the delay draw that we’ve talked about. The investors have to bear the delay draw component of those structures, and with that, the notes have to be issued in physical form. So there’s some operational burden on investors there.

Disclosure:

Note physical form means the notes are not owned electronically. Rather a notarized paper is evidence of ownership.

Allan:

There’s obviously the asset flexibility point that we talked about as well, which is a little differentiated, but then there’s the liquidity point. I think middle market CLOs have established themselves as a fairly liquid asset class at this point. They made up about 25% of the overall CLO market last year. So the acceptance of that structure across the board for investors has been broad. We’ve seen the spread basis between middle market and broadly syndicated tighten over the past 12 to 24 months. So I’d say a lot of the juice or a lot of the incremental spread for investors has come out of that. So rated feeders are a way for investors to gain some incremental spread with some of those trade-offs around liquidity, complexity, et cetera. But we obviously touched on some of the pros, the parts of ordination that we talked about being obviously a key benefit. There’s also typically a longer on-call period associated with the rated feeders, and so there are some obviously structural positives away from just the spread component that investors obviously consider and take into account.

Shiloh:

So then if we are talking about CLO equity versus rated feeder equity, would a lot of your points from the AA be relevant there where it’s a newer structure, people need to do work on it and understand it and are asking for a premium or asking to get paid a little more for doing the work, but at the same time, you’re less levered through the rated feeder?

Allan:

Yes, you are less levered through the rated feeder.

Shiloh:

So from the perspective of equity, maybe the returns model out the same because the equity investor needs to do some work, understand a new structure, but on the other hand, there’s less leverage in the rated feeder

and then maybe another con or pro, depending on how you look at it, would just be that the asset quality of the underlying loans might be different from the 95% first lien that you mentioned.

Allan:

That’s right. I think one of the key differences we touched on is obviously there’s more asset flexibility, and I think over the life of these vehicles while CLO, you’re constrained in 95% first lien, the asset flexibility given into the rated feeders over the course of a four year reinvestment period. I think there’s a lot of optionality that exists for rated feeder equity there. So I think managers have the ability to take advantage of market dislocations, of market changes, opportunities like we talked about in second liens or recurring revenue, that might come up over the course of that period that managers would not necessarily have in a more structured middle market CLO. So certainly I think the less leverage is critical, but I think one of the bigger, more interesting dynamics that we haven’t necessarily seen totally play out yet is that asset flexibility and how managers are able to leverage that to the equity’s benefit over the life of the deal.

Shiloh:

Maybe I missed it or not fully understanding, but when you say asset flexibility, you’re talking about the ability to have more second liens or other funky stuff,

Allan:

The ability to have more non-first lien assets. I won’t use funky assets, but more differentiated assets because I think one big aspect of the market is you think about second liens, there are periods of time where second liens are not that attractive or not that in vogue for managers, but there’s other times where there’s a lot of opportunity in that part of the market to pick up incremental spread for pretty attractive assets. And the same goes for recurring revenue. There’s going to be periods of time where there’s a lot of opportunity to do that in periods of time that there’s not. So the asset flexibility or the ability for the manager to really pick their spots across different parts of the market is more available on the rated feeder side.

Shiloh:

And then one last question is just should the market

expect to see a lot of new rated feeders? Is this a structure that’s going to

gain in popularity over time?

Allan:

We certainly think so. We’ve put obviously a lot of resources into the market. You’ve seen there be a slow start to the issuance of rated feeders, but I think certainly as the market develops, as the investor base continues to grow, as the process for execution of rated feeders becomes more streamlined, I think there’s definitely the anticipation that there will be incremental issuance of the product. It’s not that dissimilar to middle market CLOs 20 years ago when there was only a handful issued annually, and that’s obviously grown. I think this is a market that has the ability to really grow, maybe not to that scale, but certainly to become a large part of the overall private credit financing market over the next few years.

Shiloh:

Great. Well, Allan, thanks for coming on the podcast.

Really appreciate it.

Allan:

Thanks, Shiloh. Thanks for having me.

Disclosure:

The content here is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as legal, business, tax, or investment advice or be used to evaluate any investment or security. This podcast is not directed at any investment or potential investors in any Flat Rock Global Fund.

Definition Section

AUM refers to assets under management

LMT or liability management transactions are an out of court modification of a company’s debt

Layering refers to placing additional debt with a priority above the first lien term loan.

The secured overnight financing rate, SOFR, is a broad measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight, collateralized by treasury securities.

The global financial crisis, GFC, was a period of extreme stress in global financial markets and banking systems between mid 2007 and

early 2009.

Credit ratings are opinions about credit risk for long-term issues or instruments. The ratings lie on a spectrum ranging from the highest credit quality on one end to default or junk on the other. A AAA is the highest credit quality. A C or D, depending on the agency issuing the rating is the lowest or junk quality.

Leveraged loans are corporate loans to companies that are not rated investment grade

Broadly syndicated loans are underwritten by banks, rated by nationally recognized statistical ratings organizations and often traded by

market participants.

Middle market loans are usually underwritten by several lenders with the intention of holding the investment through its maturity

Spread is the percentage difference in current yields of various classes of fixed income securities versus treasury bonds or another benchmark bond measure.

A reset is a refinancing and extension of A CLO investment.

EBITDA is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation,

and amortization. An add back would attempt to adjust EBITDA for non-recurring items.

General Disclaimer Section

References to interest rate moves are based on Bloomberg

data. Any mentions of specific companies are for reference purposes only and

are not meant to describe the investment merit of or potential or actual

portfolio changes related to securities of those companies unless otherwise

noted.