Shiloh: Hi, I’m Shiloh Bates and welcome to the CLO Investor podcast. CLO stands for Collateralized Loan obligations, which are securities backed by pools of leveraged loans. In this podcast, we discuss current news and the CLO industry, and I interview key market players.

Today I’m speaking with Lauren Basmadjian, Carlyle’s head of Liquid Credit, where she oversees $53 billion of assets under management. The Federal Reserve began its cutting cycle in September with a 50 basis point cut, and SOFR has come down almost twice that from its highs, so we discuss how that is expected to affect our industry. We also discuss her outlook for CLO spreads, loan defaults and recoveries, and how she thinks about investing in CLOs managed by other managers. If you’re enjoying the podcast, please remember to share, like, and follow. And now my conversation with Lauren Basmadjian. Lauren, thanks so much for coming on the podcast.

Lauren: Happy to be here.

Shiloh: Why don’t you tell our listeners a little bit about your background and how you became a CLO manager?

Lauren: Sure. So I started in 2001 at a place called Octagon Credit Investors, which is a boutique below investment grade corporate credit firm, one of the oldest CLO managers. I spent 19 years there before I came to Carlyle to run the liquid credit platform. And today I run the liquid credit platform globally for Carlyle, which is about $53 billion dollars of assets under management, the vast majority of which are CLOs that are managed by Carlyle, or that we invest in other managers as well. And we are the oldest piece of Carlyle credit, so also established in 1999, and the largest liquid CLO manager.

Shiloh: So how many CLOs do you guys usually print or create in a year?

Lauren: So it definitely depends on the year. This year will be a record year for us, most likely between new issue resets and refinancings. We’ve already done 23 CLOs this year. Our record was 25 in 2021.

Shiloh: Is that high number just because financing costs are attractive today, in your view, is that the key driver?

Lauren: That is certainly one of them. When you think about how wide liabilities got after Ukraine, it really made resetting deals impossible because you were going to increase your weighted average cost of debt for the most part. So in a way you have two years of a backlog of resets and that’s part of what’s led to such an active year for issuance this year. It’s not just new issue, but as liability spreads compressed pretty immediately in January of 2024, resets started to make sense again and we had a lot of deals in the backlog for that.

Shiloh: Well, I’ve been in the backlog as well and it’s good to work through some of those deals for sure. So you’ve been in the market for a long time. What’s one or two things that you find interesting or unique about the CLO market?

Lauren: In general, one of the most interesting things, and you could probably attest to this, is though it is a trillion dollar market, so large and liquid, it still does feel like it has a niche feel to it where not everyone invests in CLOs. And I think there’s probably some reasons for that. They’re associated with CDOs, for example, but CLOs did not blow up the economy during the financial crisis, but they’re also complex and there’s no standardized documents. So it takes more time to analyze the investments and you really have to invest in staff to do that. And so even though it’s a large liquid market, there are many investors that don’t have an allocation.

Shiloh: Yeah, it’s funny. When I go to CLO conferences, I just see, even though the market’s grown so much, I really just see a lot of the same players.

Lauren: Absolutely.

Shiloh: Supposedly the market’s growing in investors as well as AUM, but I just see a lot of the same folks and that’s it. I think for me, one of the things that’s pretty interesting about the market is just, you can buy, for example, CLO equity in the primary or the secondary market, and at times these two markets just trade at totally different yields. So a lot of times primary is a lot tighter than secondary, and anybody would be able to get better risk adjusted returns by buying in the secondary for sure. But I think one of the things that accounts for the difference is just that the primary process is really the fun process. That’s the one where we’re all working together, we’ve got a manager, and there’s a warehouse and we’re trying to get the best debt execution and we’re commenting on docs. And for most people, especially newer to the CLO market, I think that’s the process that’s going to feel good to them. Whereas in the secondary, the CLO exists, some broker dealer is offering it to you, and really the only thing to negotiate is a price, and most people probably assume the dealer in between is taking a fair amount of economics for themselves. I think that just pushes a lot of people to the primary.

Lauren: And I think we’ve also seen, with the slowdown in CLO issuance in 2022 into 23, there was a very specific profile in the secondary. It was either a really high weighted average cost of debt profile that you could buy and plan on a reset or repricing, or deals that were close to ending the reinvestment period or had a shorter reinvestment period left. So in order to diversify your maturity wall of investing, I think a number of investors came back to primary where they were going to get five-year reinvestments and diversify their book a little bit. I think that, especially with the cleaner pools, led to some of that new issue demand that we’re seeing this year.

Shiloh: Are there any profiles of equity that you think have worked out particularly well? One that comes to mind would be, for me, any CLO that ramped during a period of stress where loans were bought cheaply.

Lauren: A hundred percent. Could not agree with you more. I think that we’re trained to think of CLOs as an arbitrage product.

Disclaimer: Note: By arbitrage, Lauren is referring to a CLO where the equity is owned by a third party looking for favorable risk-adjusted returns.

Lauren: Most of the time they are, but they’re also an amazing way to buy discounted loans in long term, non-mark to market financing. And if you could close your eyes when the cost of debt’s really high and just say, we’re going to buy good assets cheap, and eventually we trust that the market’s going to come back and we’ll reprice our liabilities, I think those are the best deals.

Shiloh: Agreed. And those deals are good both in the primary and then often are sold in the secondary too at compelling prices. So Carlyle is obviously one of the biggest managers, or biggest, I guess depending on how you do the cut or the stat. How do you think your platform is differentiated?

Lauren: There’s a couple things. One is we are one of the oldest managers, so you could look at our performance through multiple cycles, even back to dotcom bust, financial crisis, energy, Ukraine, inflation. So you could see how we’ve performed. Two, because we’re big, we’ve invested behind it. So we have over 20 analysts in the US over 10 in Europe. We have a five person restructuring team, which I think is a key differentiator going forward. And we’re able to do it because we have the financial wherewithal to invest in the resources. I think that’s going to affect outcomes going forward, especially as we move out of the bankruptcy court and into this liability management paradigm that we’re living in. We also are very connected internally at Carlyle and we use the One Carlyle network in our diligence and our tracking. Coming from a boutique manager, it’s really different for me. It’s amazing the access you have to deal professionals, to strategic advisors. Just being able to get on the phone with people who know the industry, know management teams, or even our Washington resources. It just really is this One Carlyle network. It sounds like a buzzword, candidly. I thought that’s what it was when I read about it before I came over. But the connectivity is really strong and we’re all looking to help each other in our investment decisions.

Shiloh: Is part of that that when you’re looking at a new loan opportunity, if it’s a leveraged buyout, that it’s very likely that Carlyle’s PE team has looked at the company and already formed a view? That’s part of your credit research and analysis?

Lauren: It is. We may have looked at it or we may own a similar company. It’s all compliance-chaperoned.

Shiloh: With you guys issuing so many CLOs, can there ever be too many or do you ever hit a point where there’s maybe just not enough demand for your CLO liabilities regardless of how well you guys are doing on the assets?

Lauren: I would think of us relative to the market. So the market has stopped growing right now. I actually think it will grow again next year. But I would think of us relative to the market and as well, CLOs traditionally take two weeks to price. And I think part of that is this non-standardized documentation, which is not going to change. But I think as a market, we need to become more efficient with a quicker process in the primary, or multiple processes at the same time. If that doesn’t happen, then I think there is a cap to how many total transactions you could do, and we’re probably nearing that cap this year.

Shiloh: Okay. And that’s because you just don’t want to be in the market with overlapping deals. You want to get one done, move on, and then the market opens back up to you again, that’s how you think about it?

Lauren: Our equity investors generally don’t want us to do that unless we have a clear path for bespoke pricing. And we are finding those paths today where perhaps we’re syndicating AAAs in the US in one deal, but have a hundred percent buyer in Japan for another deal. So they’re not competing. And I think being able to identify separate paths is the way that you could bring more than one deal at a time to market.

Shiloh: So the Fed cut by 50 bps in September. Does that matter to you at all in terms of CLO issuance or the performance of the underlying loans?

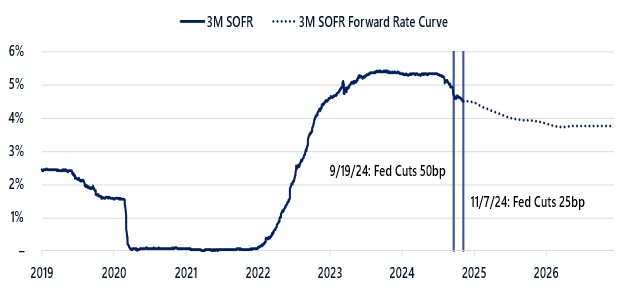

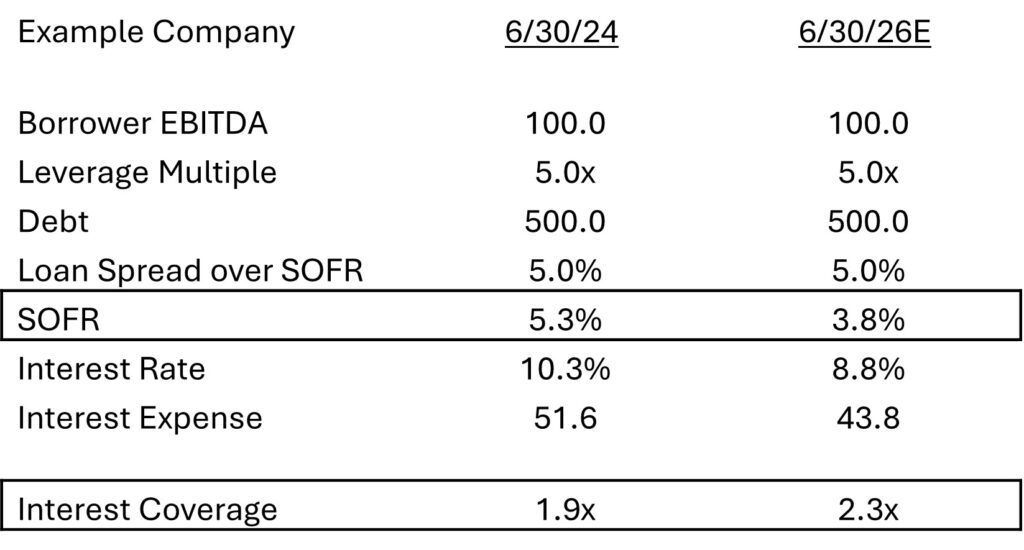

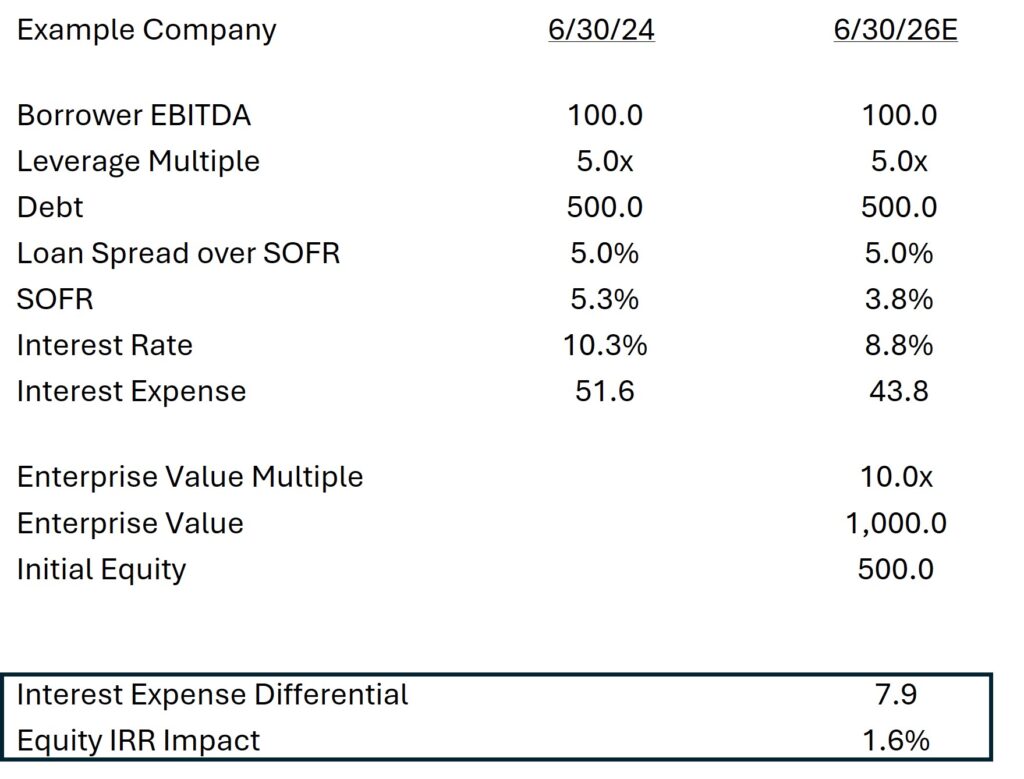

Lauren: Yeah, rates coming down matters. What I’d say is that we’re already down about 80 basis points in SOFR and that’s going to flow through to our borrowers who mostly have floating rate debt. Some of it’s hedged. But you’re going to start to see that come through in the fourth quarter. And if you see further anticipation of cuts, SOFR likely comes down even before the cut. And that’s real cash benefit to our companies. I think that also leads to less downgrades, or dare I say, even upgrades, eventually, for the underlying loan borrowers. So those are the positives. There is an effect to CLO equity with rates coming down. CLO equity has benefited from a higher base rate, but we all use the forward curve in our modeling. And so right now we’re looking at terminal rates around three and a half percent in our models. To me it’s a question of is it higher or lower than what the curve is expecting versus how many more cuts because the curve is anticipating cuts, which is then flowing through into the CLO equity pricing.

Shiloh: Yeah, I do a fair amount of education with our investors on this. And then the idea is that when you buy CLO equity, it’s a string of cash flows and to model that, you’re looking at a forward curve. So we’re already budgeting for the fact that rates are expected to come down. That’s already in the projection. It’s already been in the projection for some time, which is very different from owning loans directly. When rates come down, you just get less in income and that’s it. There’s no forward projection or anything like that. And I guess the other part of it, the other thing we’re reserving for in CLO equity is just that we assume that, I think most people assume 2% of the loans will default each year and the recovery will be around 70, maybe a little short of 70 depending, but is two and 70, are those numbers from the past or do you think those are numbers that you can still hit or how do you think about it?

Lauren: I think it’s numbers from the past, but probably for maybe a different reason than what people are anticipating. There are very few in-court bankruptcies now and where a lot of street analysts expected us to jump to three, four, 5% after Ukraine, it didn’t happen, right? And today we’re around 80 basis points, but what’s happened in the last year and a half is distressed exchanges, discount capture, liability management, whatever you want to call it, where a borrower comes to you and says, “Hey, your credit agreement’s really loose. We’d like you to give us some discount. Us as equity, we’re not taking a loss before you are. You, debt holder, you’re going to take the loss and then you could close up the document and I won’t strip assets for you. I won’t dilute the value of your collateral.” And so that’s become commonplace. Before you had transactions that offended everyone and we all knew the names. It was J Crew or Chewy, and we all talk about them with brand names, but there’s been dozens of those now. And when I think about it, I think there’s more that’s going to be out of court. I think bankruptcies are going to be fewer, so we won’t be at an average 2-3% going forward. What I’d say if there’s any positive to that is that companies are generally asking for outside of court. It is very different and a much lower impairment rate than what we’ve seen historically for bankruptcies. So on average, the range that you’re usually seeing for the discount or the impairment out of court has generally been around two to 20 cents with the average a little over 10. So I think you almost have to think about a higher percent when you include the out of court stuff, but also a higher recovery because you’re not taking the same type of haircut off this.

Shiloh: So if I’m modeling CLO equity and I use a 2% default rate and a 30% loss given default, so that’s like 60 bps and that’s really the key number, like, I hope it’s lower than 60, but whichever way of the two variables we get there is fine by me. Do you think 60 is optimistic over the next year or two, or how would you think about that?

Lauren: I think it’s realistic, but here’s this other thing about the difference in how the market is changing is, before, if you owned a loan, you got the same recovery no matter what manager owned it, manager A owns a loan, manager B owns a loan, and they both get 60 cents back. And with more of these out-of-court processes, you are seeing groups that are put together to be a majority and be able to extract more value and better recoveries out of the process. Generally speaking, these are larger managers that are important to bankruptcy advisors, companies, sponsors, or they just have the right to be in there because they’re so big and they’re a top five holder. So I do think that the best thing to do is just avoid the bad credits, but that’s very difficult to do in totality. The second best thing to do is get in the right groups. And so you could see that 60 basis points, maybe even if they own the same loan, same exact loan by different managers, you could see some managers have a 20 point swing on recoveries based on what groups they get into.

Shiloh: Do you think on these out of court restructurings that there’s a difference in private equity firm DNA and that some naturally are going to gravitate towards trying to get their first lien lenders to take a discount and others maybe are more old school and that’s just not how they’re thinking about the agreement between debt and equity?

Lauren: I think that before there were a lot of sponsors that were worried about being viewed as a bad actor and what would that mean as they continue to do deals and their access to capital. I think unfortunately the advisors in general have done a really good job of convincing companies and sponsors that this is common practice and it’s not going to be viewed as egregious. If they did it with all of their companies, or half of their companies, sure, that’s a problem. They may be cut out of the market, but to have one, two or three, it’s acceptable. And so I think sure, they’re probably a select group of sponsors that still view lenders as partners, but for the most part I think that’s done.

Shiloh: I think I’ve heard one private equity firm say that actually they think it’s their fiduciary responsibility to try to put it to the lenders when they can. It’s like, oh, wow.

Lauren: To preserve the equity. Right, they’re fighting for the equity. I have heard that as well.

Shiloh: It’s an interesting way to think about it. So I imagine around Carlyle you buy a lot of, or your firm buys a lot of CLO securities, many that are not managed directly by you, is that correct?

Lauren: That’s correct.

Shiloh: Are you involved in that process?

Lauren: Yeah, I sit on the investment committee for that.

Shiloh: Okay. And how do you think about what’s interesting to you and what managers you want to partner with in that?

Lauren: So we have a team between structurer, traders, analysts that are looking at third party opportunities, so buying debt or equity and other managers’ CLOs. One of the things that we do is a deep dive on the portfolio because we do lend to a lot of companies and we have this huge research team. We try to incorporate their views. We even look at our view of WARF, meaning, well, we have our own rating system.

Shiloh: WARF is the weighted average rating factor.

Lauren: Right. The Moody’s equivalent, the numerical equivalent of the letter rating. And then we create a Carlyle one and say, well, our analyst team thinks this portfolio is riskier or safer than what the market is seeing, and we’re using our name-by-name analysis to do that. So that’s one thing. But I’d say in general we want to see consistency of performance. I mean, as you put together a portfolio of investments, we’re buying certain managers for their attributes. Maybe one is a lower spread manager, what we think is really stable, great historical default rates, and then we have another manager that we think is Alpha where they do take more risk, but we get compensated in the total return for that. What we get concerned about is when we see style drift from managers, and that’s what we try to identify early.

Shiloh: What securities generally work for you guys at Carlyle? Are you putting equity and BBs into GPLP funds?

Lauren: Yeah, we have a number of funds that invest across the capital stack. I’d say that it looks more like SMAs for investment grade, but we have retail products for lower tranches. So we have a fund called CTAC, which is a cross-platform credit product at Carlyle, but part of that fund is CLO equity and CLO double Bs. We have a public equity fund that is CLO equity. So we find different fund structures work better depending on the tranche, and we try to marry the liquidity needs, the investor needs by fund with the right end investment.

Shiloh: You do a pretty heavy overlay I imagine, where you just look at somebody else’s CLO and just kind of determine, hey, what percentage of these loans are approved by you or sitting in your CLOs? I imagine that weighs pretty heavily.

Lauren: We do. We have to be careful to just think that our view is always right and just buy the loans again that we like. But yes, absolutely. I think it’s actually more helpful on the bad loans, if that makes sense. So things that we passed on or think could have trouble, but the price doesn’t reflect that yet. And maybe we do own that loan and that could be the case too, but I think that it’s really identifying that tail risk that makes more of a difference in saying, yes, these 100 credits are totally fine.

Shiloh: So a substantial majority of my investments are in middle market CLOs. Is that something that you’re involved in?

Lauren: And that’s such an interesting space because it’s growing rapidly where the rest of the CLO space is a little stagnant right now. Traditionally, as you know, you’ve had most of CLO equity that’s for middle market or private credit CLOs be captive or financing trades, and you would place the debt through more traditional routes. Still today, a lot of middle market CLOs or private credit CLOs are financing trades, but you’re seeing third party equity interest because the cash flows are better because the arbitrage is much more robust than in liquid credit CLOs. So we are looking at that. We’ve issued a private credit CLO this year, but it’s been a financing trade. We’ve done another reset of an existing one, but we are taking a look at what a third party model looks like for private credit CLOs, meaning should we be issuing private credit CLOs with investors like you?

Shiloh: You should be. That’s my opinion. Are you involved in that? So the selection of middle market loans for CLOs around your platform, is that something that you’re also involved in or is that a separate team?

Lauren: So it is a separate team. We have a totally separate analyst team for direct lending and private credit. Our teams talk a ton and you’ve seen more movement of loans between the two, more idea generation between the two. But there’s a fully built out direct lending team. That said, I do sit on the investment committee for private credit as well. So I am approving the loans that we’re buying, but the team doesn’t report into me. It’s really a collaborative effort across the platform. And also it’s really beneficial for me to see, as a liquid investor, what’s happening in the private markets and it gives me an idea of what could be refinanced there, for example, or what kind of profile of loans they’re looking for. So I joined maybe two years ago and I think it’s been really additive to my thought process when investing in liquid credit.

Shiloh: Was it kind of a little bit of a shock or a surprise? If you go from liquid credit where, I don’t know, the EBITDA numbers for a borrower might be a hundred million plus, and then you find yourself somewhere where people are making loans at like 20 million of EBITDA, maybe with better covenants, maybe with a better LTV and better docs.

Disclaimer: Note LTV means loan to value and Shiloh should know better than using three letter acronyms in his podcast.

Shiloh: But still the difference in company size is substantial. Is that kind of an easy thing to get your head around or how did you think about that?

Lauren: So no one’s ever asked me that question. It is so hard. It was hard for me to look at these companies and say, how do you lend to a company that’s like you said, twenty million dollars and buy and hold it?

Shiloh: Yeah, no liquidity.

Lauren: That’s right. Where in liquid markets, one, the average EBITDA of a company is a billion dollars at this point, and two, I could sell it if I changed my mind or all these things changed. So how do you underwrite to buy and hold? And that did take me a while. It took me at least a few months to get used to looking at the deals, thinking about them differently. I will say there’s a different level of information that you could get, diligence. Obviously the documents are way better and tighter than you see in liquid. There’s still a relationship with sponsors that I think we’ve lost in the BSL market. And so when we were going through Covid and then inflation, what was very clear is that we were seeing a lot more equity checks come in into direct lending from sponsors to support the companies than really I’ve ever seen in the liquid market. So I think I had to get used to looking at those smaller companies, but also with a lens of all the extra protections that we get by doing that.

Shiloh: What do you think is a good premium to get paid if the loan has no liquidity at all and you’re going to hold it to maturity versus having kind of the broadly syndicated liquidity? What do you think that’s worth in basis points?

Lauren: So today I’d say we’re at 350 for the liquid market and you’re seeing private credit go down to 500, 525 for good credits.

Disclaimer: Note: Those numbers were spreads over SOFR in basis points.

Lauren: And that does feel a little tight. Now we’re both repricing, so the spread may change shortly again, but I think that you would generally want at least 200 basis points for that illiquidity premium. It’s illiquidity and size. Maybe I’m still stuck on that size thing that you asked about in the last question because I think that there are some of these hybrid private credit BSL issuers that they have a billion dollars of EBITDA and they’re really big companies, but they chose to access the private credit market. I think those probably should have less of a spread premium than the true middle market universe.

Shiloh: Is there anything else happening in CLOs or your platform that you think would be interesting to discuss?

Lauren: I think the most interesting thing is just the continued evolution of these liability management exercises. To me, we went from a covenanted market to cov-lite after the financial crisis, and this is the next sea change for me where we went from if you had a problem, you’re doing it in court to now seeing, even if you don’t have a huge problem doing it out of court, and seeing our documents used against us to advance more money if a company needs it or take a discount capture. I think that’s the big theme out there. Where I would say that’s positive is we lend to 600 companies in the US, over 200 in Europe. Our data is pretty good, I think probably better than index data. We see so many private companies and the resilience has been impressive. As we’ve said, the companies have been through so much in the last four years. Low investment grade corporate credit should be really hurt by higher interest rates because they have a lot of floating rate debt. And we’ve seen the percentage of our companies that produce cashflow is way higher today than it was a couple of years ago, like in 2021 for example, which seems counterintuitive because rates are so much higher and growth has slowed, but it’s because companies are focused on it. And it’s amazing that when management teams focus, they can start to produce cashflow. They’re figuring out how to become more efficient, maybe cut back on CapEx or hiring, but about 70% of our companies are producing free cashflow in this higher rate environment. We haven’t seen third quarter numbers yet, but for the second quarter, average sales growth of about 5% and average EBITDA growth of 10%. So I think there’s been pretty resilient market in the face of a lot of negativity of downgrades and distressed exchanges, but companies are figuring out a way for the most part to make it work.

Shiloh: One last question. Do you expect that CLO liabilities will continue to contract here going into year end or they’re kind of in the middle of a lot of these conversations, I imagine?

Lauren: I do. There’s so much supply, so I think it would be tightening much further if there wasn’t as much supply. But that said, AAAs have had negative issuance, net issuance, because the pay downs have been so intense for AAA buyers year to date from amortization of post reinvestment period deals and call deals and resets and refinancings. So I think as that market has shrunk and it’s performed really well, we’ll see continued demand to redeploy that money and I think that leads to continued tighter spreads especially. And then the rest of the stack, usually CLOs figure out a way to work, and loans are repricing.

About half of our portfolio has repriced year to date with an average reduction in spread of 44 basis points. That means we lost 22 basis points on average in spread. Liabilities have to reprice too to make the arbitrage work.

Shiloh: That’s right. Great. Well, Lauren, thanks so much for coming on the podcast. It was great to talk to you.

Lauren: It was a pleasure. I really appreciate you inviting me.

Disclaimer: The content here is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as legal, business, tax, or investment advice, or be used to evaluate any investment or security. This podcast is not directed at any investment or potential investors in any Flat Rock Global Fund.

Definition Section

AUM refers to assets under management.

LMT or liability management transactions are an out of court modification of a company’s debt.

Layering refers to placing additional debt with a priority above the first lien term loan.

The secured overnight financing rate, SOFR, is a broad measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight collateralized by treasury securities.

The global financial crisis, GFC, was a period of extreme stress in global financial markets and banking systems between mid 2007 and early 2009.

Credit ratings are opinions about credit risk for long-term issues or instruments. The ratings lie on a spectrum ranging from the highest credit quality on one end to default or junk on the other. A AAA is the highest credit quality. A C or D, depending on the agency issuing the rating, is the lowest or junk quality.

Leveraged loans are corporate loans to companies that are not rated investment grade.

Broadly syndicated loans are underwritten by banks, rated by nationally recognized statistical ratings organizations, and often traded by market participants.

Middle market loans are usually underwritten by several lenders with the intention of holding the investment through its maturity.

Spread is the percentage difference in current yields of various classes of fixed income securities versus treasury bonds or another benchmark bond measure.

A reset is a refinancing and extension of a CLO investment period.

EBITDA is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization.

An add back would attempt to adjust EBITDA for non-recurring items.

ETFs are exchange traded funds.

LIBOR, the London Interbank Offer Rate, was replaced by SOFR on June 30th, 2024.

Delever means reducing the amount of debt financing.

High yield bonds are corporate borrowings rated below investment grade that are usually fixed rate and unsecured.

Default refers to missing a contractual interest or principle payment.

Debt has contractual interest principle and interest payments, whereas equity represents ownership in a company.

Senior secured corporate loans are borrowings from a company that are backed by collateral.

Junior debt ranks behind senior secured debt in its payment priority.

Collateral pool refers to the sum of collateral pledged to a lender to support its repayment.

A non-call period refers to the time in which a debt instrument cannot be optionally repaid.

A floating rate investment has an interest rate that varies with an underlying floating rate index.

General Disclaimer Section

References to interest rate moves are based on Bloomberg data. Any mentions of specific companies are for reference purposes only and are not meant to describe the investment merits of, or potential or actual portfolio changes related to, securities of those companies unless otherwise noted. All discussions are based on US markets and US monetary and fiscal policies. Market forecasts and projections are based on current market conditions and are subject to change without notice. Projections should not be considered a guarantee. The views and opinions expressed by the Flat Rock Global speaker are those of the speaker as of the date of the broadcast and do not necessarily represent the views of the firm as a whole. Any such views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions, and Flat Rock Global disclaims any responsibility to update such views. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, or investment advice. It is not a recommendation offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. Neither Flat Rock Global nor the Flat Rock Global speaker can be responsible for any direct or incidental loss incurred by applying any of the information offered. None of the information provided should be regarded as a suggestion to engage in or refrain from any investment related course of action as neither Flat Rock Global nor its affiliates are undertaking to provide impartial investment advice, act as an impartial advisor, or give advice in a fiduciary capacity. Additional information about this podcast along with an edited transcript may be obtained by visiting flatrockglobal.com.