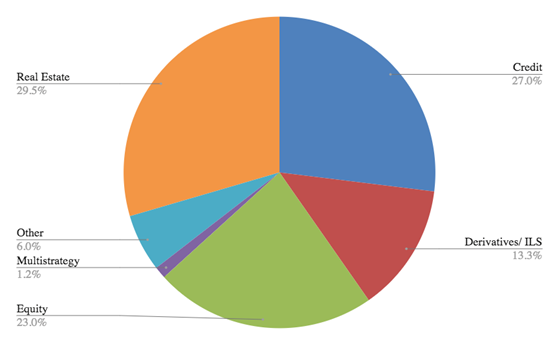

As reported by the SEC, there are 68 active interval funds offering unique access to less liquid investments including real estate, mortgage-backed securities, corporate debt, and structured products. The chart below shows the current makeup of these active interval funds, which total $33.5 billion in net assets.

Fig 1. Source: intervalfundtracker.com

Liquidity

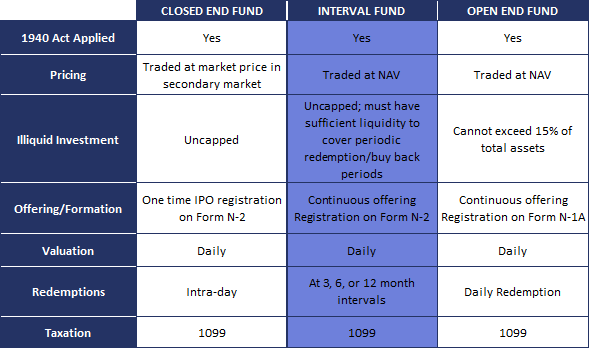

Interval funds are a type of closed-end fund. They offer more liquidity than traditional closed-end funds and less liquidity than open-end mutual funds. Per the Investment Company Act of 1940, open-end funds are prohibited from investing more than 15% of their net assets in illiquid assets. Closed-end funds are uncapped and able to invest the entirety of their portfolio in illiquid assets. Interval funds provide a unique alternative to these typically binary options. While interval funds are uncapped and allowed to invest beyond the 15% concentration limit on illiquid assets, they do offer investors periodic liquidity through tender offers that are typically quarterly. Interval funds’ liquidity is limited and for all intents and purposes should be considered a less liquid investment designed for long-term growth. However, compared to similarly illiquid asset structures found in closed-end funds or GP/LP structures, interval funds offer a better liquidity profile.

Below is a chart to summarize the key attributes of closed-end, interval fund, and open-end fund structures:

Repurchase Period

At the predetermined buyback period, interval funds will announce a percentage of all outstanding shares they are willing to buy. This percentage is usually close to 5% but can be as much as 25%. These repurchases are done pro-rata, meaning fund managers allocate all repurchases proportionally and there is no guarantee an investor can redeem the number of shares they want to during that period. This repurchasing structure restricts selling opportunities and reduces liquidity. However, it also reduces the risk that the fund manager becomes a forced seller of assets potentially incurring unnecessary losses.

Why Invest in Interval Funds?

- Interval funds allow investors to capture the illiquidity premium available in less liquid asset classes, while still investing in an SEC regulated entity and maintaining some level of liquidity.

- Interval funds make less liquid asset classes, typically reserved for institutional investors, available to retail investors without the accredited or qualified investor limitations.

- Using interval funds, asset managers can adopt alternatives investment strategies with greater liquidity than typically found in GP/LP investment structures and stronger regulatory oversite than a GP/LP structure. GP/LPs are often structured with draw down provisions that make for an inefficient use of capital as investors retain cash in anticipation of capital calls.

Interval Fund Risks

- It’s important that investors understand the liquidity limitations of interval funds. You get the benefit of expected higher returns in exchange for less liquidity. As a result, interval fund investors should have longer term investment horizons.

- Investors should also understand how a particular interval fund is structured to address its liquidity needs. The fund should have sufficient cash, cash flow and/or liquid assets to meet the periodic tenders.

For further information feel free to email info@flatrockglobal.com