Ted: Hello, I’m Ted Sades and this is Capital Allocators. This show is an open exploration of the people and process behind capital allocation. Through conversations with leaders in the money game, we learn how these holders of the keys to the kingdom allocate their time and their capital. You can join our mailing list and access premium content@capitalallocators.com.

All opinions expressed by Ted and podcast guests are solely their own opinions and do not reflect the opinion of capital allocators or their firms. This podcast is for informational purposes only and should not be relied upon as a basis for investment decisions. Clients of capital allocators or podcast guests may maintain positions and securities discussed on this podcast.

Ted: My guest on today’s sponsored insight is Shiloh Bates, the Chief Investment Officer at Flat Rock Global, an alternative credit manager specializing in the junior tranches of CLOs. Last year, Shiloh published CLO investing, a comprehensive review of the structure, payoff rules and historical performance of the space. Our conversation covers shiloh’s 25 years spent in and around the space, an overview of the market characteristics of CLOs, attractiveness of CLO equity relative to other credit opportunities and flat rock’s approach to investing in CLO Equity and double Bs before we get going. It’s springtime in New York and that means it’s time for Yankee Baseball. Like each of the last 53 years, I’ve started dreaming about a perfect season with the Yankees finishing 162 and oh, now that’s never come remotely close in the history of Major League baseball and it never will. But after watching the Yankees sweep the Astros on the road, the first four games of the season, thanks to the Fielding and hitting exploits of star Signi, Juan Soto, I’ll quote the great comedian Jim Carrey in the movie Dumb and Dumber.

So you’re saying there’s a chance it’s highly likely by the time you’re listening to this that the perfect season will have ended, but in this moment I’m still dreaming. So as the weather turns and you find yourself outside enjoying the sunshine, but a little sad that your baseball team, hopefully the Yankees won’t be perfect again this year. At least you can turn to that podcast app on your phone and listen to Capital Allocators for about as perfect an hour as you can get each week. Thanks so much for spreading the word. Please enjoy my conversation with Shiloh Bates. Shiloh, great to see you. Thanks for doing this with me.

Shiloh: Yeah, great to be here with you.

Ted: Why don’t you take me back to your background and how that brought you into the world of structured credit?

Shiloh: Sure. So I went to Graduate school at Harvard and after graduating I went to work for Wells Fargo as an investment banking analyst, and then at Wells Fargo, basically I think somebody in HR takes a pool of a hundred different investment banking analysts and just assigns them to different groups. I was in financial institutions and one of my initial projects in the group was to work on a financing for a CLO manager. And then two years later actually found myself working for that same CLO manager in Los Angeles. So I worked as a most banking analyst for just a little bit and then quickly transitioned to the buy side.

Ted: When was that?

Shiloh: 1998 when I graduated from grad school and started in the business

Ted: What did the CLO world look like in 98?

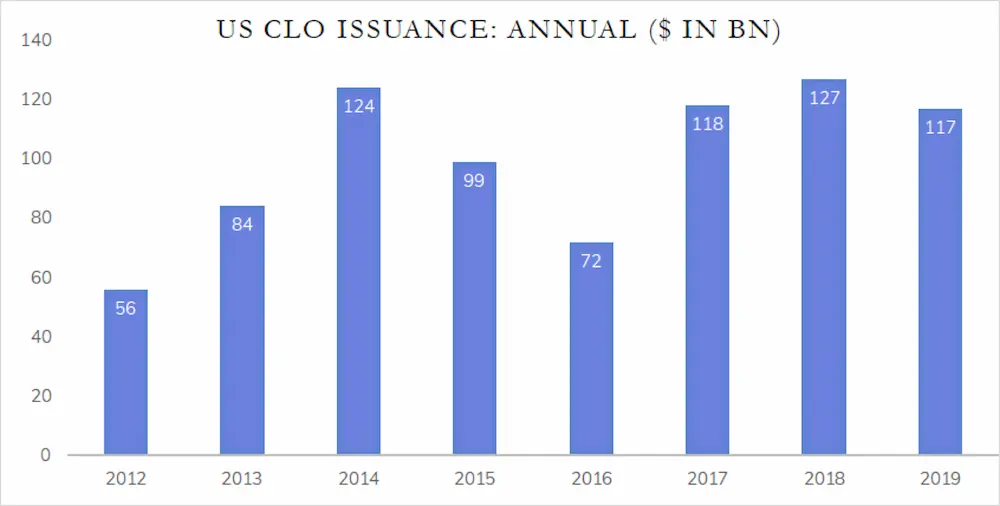

Shiloh: So it was a very small little niche of finance. So there was basically about 6 billion in a UM when I joined, and there was six different CLO managers. And today there’s really over a trillion in CLO AUM and about a hundred different active CLO managers.

Ted: So within the 1 trillion of CLO assets. How big is the CLO equity tranches across the industry?

Shiloh: A trillion of CLO AUM The CLO equity tranche is about 10% of the CLO’s financing, so it’s a hundred billion asset class for CLO equity in particular.

Ted: So what was your early experience like in that niche market at the time?

Shiloh: So basically I was a credit analyst picking loans for the CLOs. So there might be 10 or so different loan opportunities that would come across your desk in a month, and your job is to sort through the best opportunities. So the typical loan that goes into A CLO is going to be a first lien and senior secured loan. Today, the loans pay around SOFR plus three and a half to 4%. And basically the idea is that if you’re investing in first lien loans, you’re starting off with a loan to value of around 40%. So you’re not so sensitive to whether or not the economy grows at 2% or 3% or even shrinks a little you’re exposed to is really the situation where the wheels fall off the cart in terms of the company’s business model. So loans with a 40% initial loan to value, they do default, rarely, fortunately. Usually it’s due to some regulatory or technological change or loss of big customers. But as the credit analyst job to sort through the downside risks of the loans that go into the CLO and figure out the ones that survive really, and if there’s a pretty substantial downturn in the economy.

Ted: So from that early experience, looking at a very niche market at the time, what did you see in the evolution of CLOs alongside the rest of structured credit between then and when you started Flatrock?

Shiloh: The growth of CLOs has really been driven by a few factors. So one is that investors, they find lien loans very attractive today, the yield on these loans are close to 10% or higher. So people look at that and say, Hey, if I can get an equity like return and I’m the top of the capital structure, I’m first lien and I’m secured, that’s an opportunity I want to participate in. So in CLOs, people are looking for actively managed exposures to these pools of loans. And then the CLO O securities really up and down the stack have performed very well over the last 30 years. So a lot of people have seen the movie The Big Short, the CLO industry is sometimes painted with the brush of the performance of CDOs, where during the GFC you’d saw defaults really all the way up to AAA securities and initially rated AAA.

Shiloh: And then if you were in Contrast and investor in CLO equity through the financial crisis on a buy and hold basis, a lot of the equity in those deals return high 20% returns, and the debt in the CLOs defaults rarely as well. So performance has been very good over the last 30 years, so that’s going to attract a lot of investors. And then I think the final thing is that pretty much every security in the CLO market is floating rate. So we’ve been benefiting as the federal reserves have been increasing rates, and when you buy A CLO security, you just don’t have the interest rate duration that you might have if you’re buying a high yield bond or an investment grade bond. If you look at the banking crisis of the spring of last year, look, if banks would’ve owned AAA rated CLOs instead of some of the bonds that might be in the Bloomberg aggregate bond index, CLO aaas might’ve traded to 97 cents on the dollar or something like that. Investment grade IG bonds traded into the eighties and sometimes lower. So I think it’s a confluence of all those factors drawn people to the asset class and the reason that I think it’ll continue to grow.

Ted: What was your path from that early experience alongside those cycles in ls?

Shiloh: So initially my job was again, just picking the loans that go into the CLOs. So I did that for about 10 years and then I had opportunity to start investing instead of the loans investing in CLO securities directly. So I started buying CLO double B notes, which are backed by pools of leveraged loans, and then eventually made my way to investing in CLO equity, which is the riskiest part of the CLO trade, if you will. And then the firms that I work for fortunately just saw a lot of growth and that enabled me to expand my skillset and to be one of the larger players in this space over time. So that’s been a lot of fun and I’ve been fortunate in that.

Ted: What was the genesis of writing a book on CLO investing?

Shiloh: So in my role, I spend 80 or 90% of my time investing, but I do need to do some investor education. And during the covid period where I had some extra time on my hands, I decided to just write a little ebook that was 60 pages and we put it on my firm’s website and it described how I go about CLO equity investing. And after I did that, I was really surprised by how many people read it. It was widely circulated in the market, and that gave me the idea of doing a full book. So the book’s, 220 pages, a lot of the writing from it at least initially just came from stuff that we use to educate investors in our pitch decks or our q and as with them. And at the end of the day, it’s like a trillion dollar asset class market now there should be a book. So we wanted to lead with that, and I wrote it in a way where I think people that are familiar with financial concepts, no CLO knowledge is required, just the basic financial concepts, and I think people can benefit from it, and it’s all in there. If you wanted to learn about CLOs a different way, you could do Google searches and there’s tons of different articles, but I tried to make this book the one-stop shop, if you will, for all your CLO knowledge needs.

Ted: I’d love to dive in a little bit maybe through your book about what these investment opportunities are today. So we talked about what the assets are in these pools. Why don’t you talk some about what is involved on the right hand side of these balance sheets?

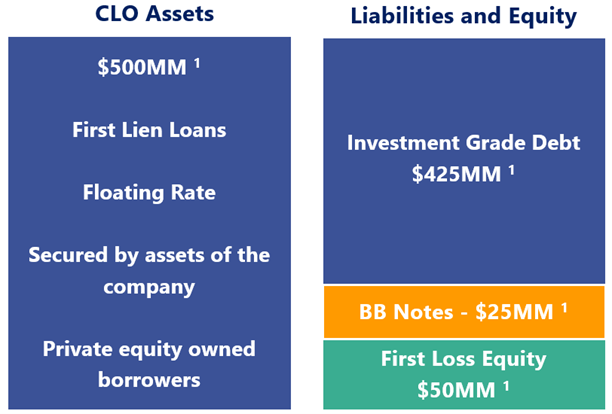

Shiloh: So the easiest way to think about A CLO is that it’s a simplified bank. So if you buy a share of, for example, bank of America or JP Morgan stock today, basically you’re going to get exposure to maybe 20 or 30 different lines of business. But in ACL O, it’s really just a pure play lending vehicle. So the CLO might have 500 million of assets in it. Again, the loans are almost exclusively first lien floating rate loans. And then to finance that pool of loans, there’s long-term financing and it’s sold in tranches, which are rated AAA at the top, and that’s most senior and secured. And then down to double B, which is the junior most CLO debt tranche. And then there’s the CLO equity, similar to my bank analogy. The loans that the CLO owns its assets, they pay much higher rate than the CLO O’S financing costs.

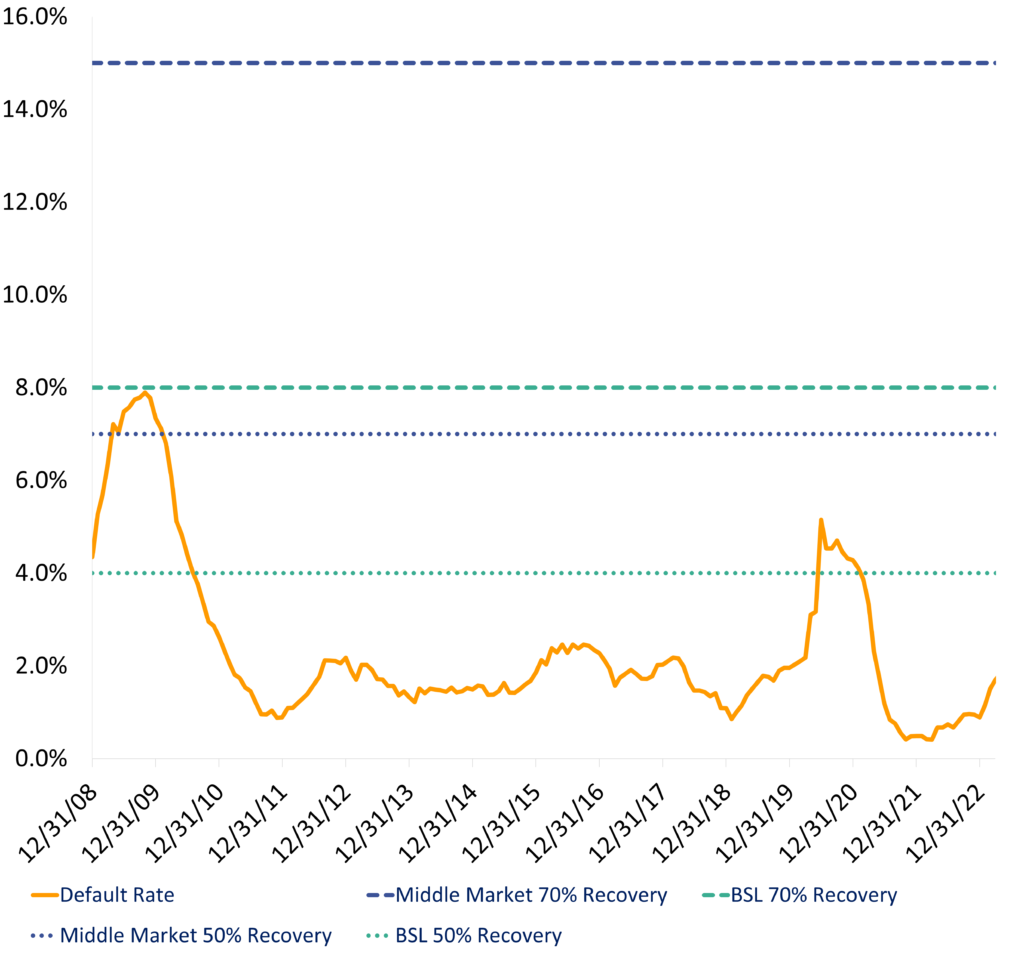

Shiloh: So that means each quarter there should be a nice amount of profitability that flows to the CLO equity. After all the CLOs debt has been paid and there’s a CLO manager as well that earns a fee, take a look after all the loans in the CLO. So if you’re an investor in CLO equity today, you’re targeting returns in the mid to high teens and basically you’re exposed to any loss on the CLOs loans. So the risk that you’re taking is loans in the CLO default, but fortunately it’s not a unquantifiable risk. It’s you can look back 30 years and by our estimate, the default rate in CLOs is about 2%. So whenever somebody buys a CLO equity tranche, we budget in a 2% default rate into all of our profitability projections. So in ACL O, you might have 200 different loans in there. I’ve never met a CLO manager who goes 200 for 200 unfortunately.

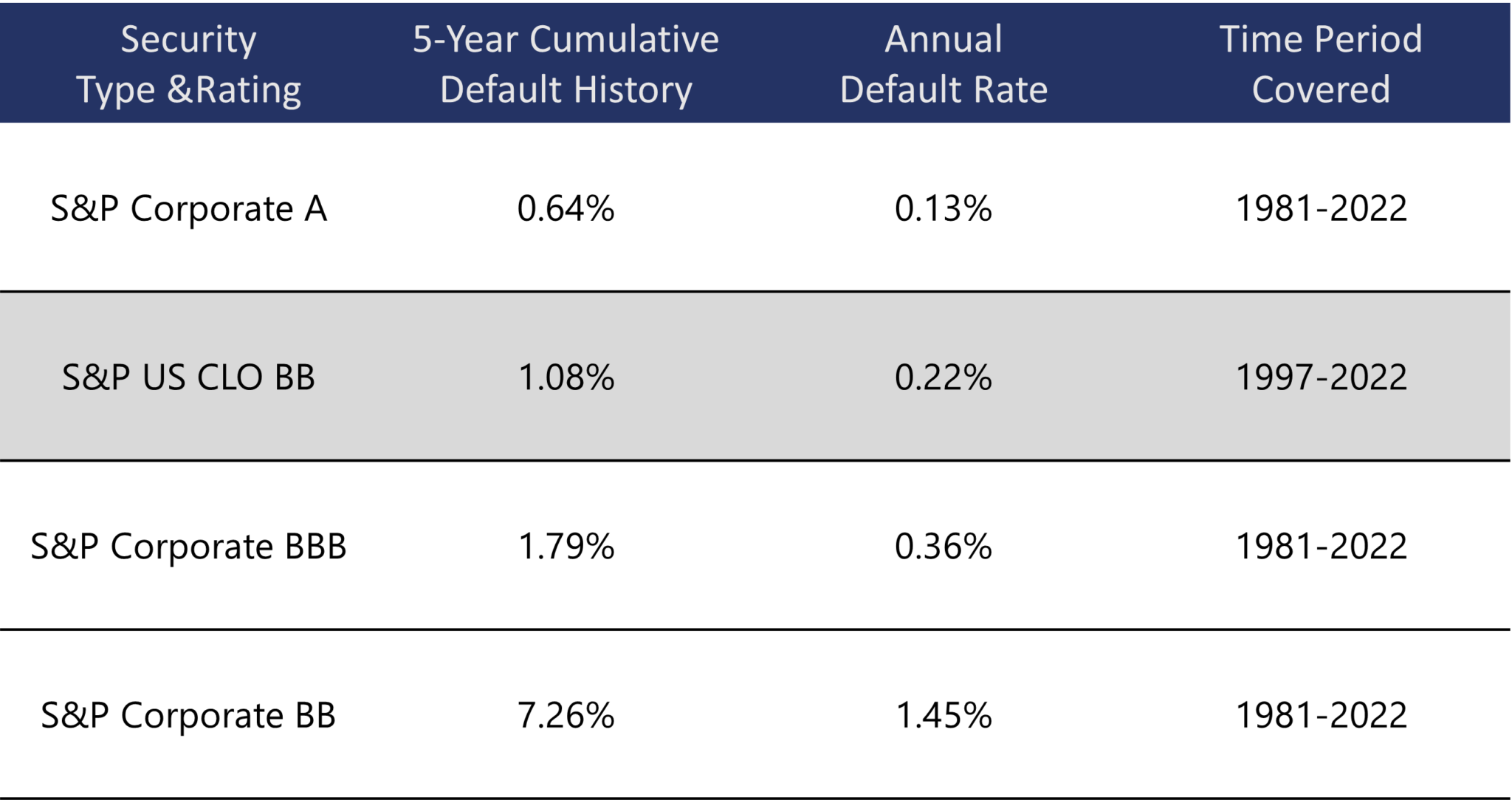

Shiloh: So you kind of budget in a 2% default rate. That’s the game in CLO equity, and that’s supported by very high quarterly cash distribution. So unlike owning SOC and the s and p 500 where you’re counting on capital appreciation maybe as being the biggest part of the return you get in CLO equity, it’s actually the quarterly distributions that come to you right away. So that’s the equity trade in a nutshell. We’re also investors in BB rated notes that works differently. That’s just a debt security where all the loans in the CLO are pledged to you as collateral. There are other debt investors in the CLO that are ahead of you, but if you look back over 30 years, the default rate on CLO BBS is around 20 basis points. So if you compare that to high yield bonds or to levered loans, if you’re just talking about the default rates of indices in general, not what’s in CLOs in particular, but high yield bonds default to like 3% per year loans, and the loan index defaults around 3% per year. So this is really just a small fraction of the default rate. And then today, because C double Bs are floating rate, and because the Fed has hiked so much, we’re getting yields in the 12% plus area and defaults have been really, really minimal. So that’s a pretty compelling opportunity that we’re going after today.

Ted: How do you pencil out? On the one hand, most of that 30 year history was in a declining rate environment. It’s a pretty stable economic environment with lower defaults, so that could be a negative if defaults go up. On the other hand, with rates going up and you own floating rate paper, you’re going to have a higher yield. How do you think about going forward, the balance of those two foror an owner of the underlying loans?

Shiloh: Higher rates is great to the extent that the borrower can make the payments. How we think about that is, well, the initial loan to value, it’s around 40%, maybe 50% at the max. So there’s a lot of junior capital and equity that supports the business. So these loans are created in leveraged buyouts where a large private equity firm, they’re buying a company and they might put up, call it half of the equity or purchase price from the perspective of the borrower, they can either make their interest in principal payments or they can toss the lenders the keys. Those are really the only options. So because the loan to value starts off, we think pretty attractive place, even as rates have gone up, borrowers still have the capacity to make the payments, and even if they didn’t, from the perspective of the private equity firm that owns the company, they’re looking at a future interest rate environment that should be decreasing.

Shiloh: At least that’s what the SOFR forward curve would say. So they would be highly incented to support a business that has decent prospects, that has a good business model, help them make the higher interest payments rather than just turning over the keys to the lender. So that’s for the underlying loans that are in the CLO, depending on the pool of loans in the CLO, you’re still going to see interest coverage ratios. So that compares the amount of cashflow the business produces each year to its annual interest expense. For the most part, the loan pools are going to be above two times, which is still pretty comfortable.

Ted: What are some of the nuances in investing in this space that led you to select the areas that you?

Shiloh: One of the things that’s interesting to me about CLOs and why I gravitated to this segment of the leveraged finance market is it’s very quantitative. In graduate school, I studied statistics among other things when we’re buying a double B note, instead of asking ourselves, Hey, is this one loan a great loan? Is it a defensible business model? Does it have a good management team? Does it have a good competitive position? These are things that we could debate you and I for hours. I don’t know if there’d be a right answer, wrong answer at the end of it, but in CLOs is very different. Hey, I have this pool of first lane senior secured the loans, and as long as seven or 8% of the loans don’t default each year for the next seven or eight years, I’m going to be money. Good. That’s the analysis you can do as a debt investor in CLOs, and I’ve always found that the analysis of pools rather than one specific outcome to be more interesting to me.

Ted: You mentioned at the onset that there are now a hundred different managers of CLOs. I’d love to map out what this investment universe looks like. So of these hundred that create these and manage the CLOs, who are these organizations?

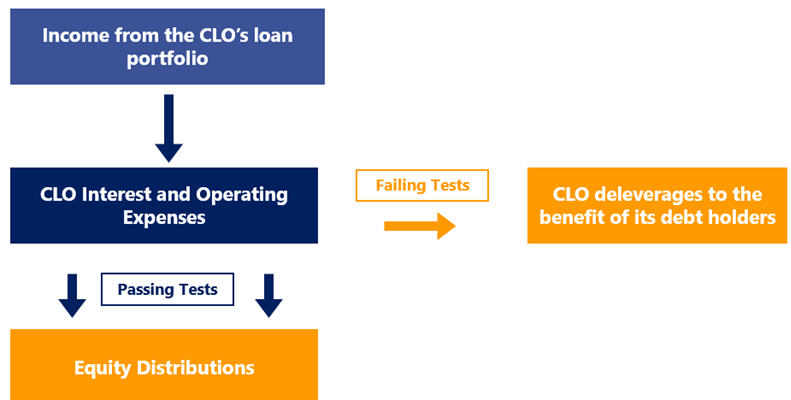

Shiloh: So the biggest alternative asset managers are all going to have large CLO groups. So Blackstone, BlackRock, KKR, Aries, they all have CLO management teams. They earn call it 30 to 50 basis points to put together the initial loan portfolio to keep the CLO fully invested during its reinvestment period, and really to make sure the CLOs passing all its tests. So the CLO managers are competing amongst themselves for capital from people like me. So they do that by having the best performance of the underlying loans in their CLOs, and they also do it by getting the best debt execution on their CLOs. So for me, that’s the two things. Those are two really of the key ingredients that make for good CLO equity returns and also for a nice stable performance of BB rated notes.

Ted: What drives the ability of the manager to get attractive financing?

Shiloh: So the best financing for CLOs comes out of Asia. It’s large Japanese banks and insurance companies that like to buy the aaa and basically they have approved lists, so they have 10 or 15 guys that have somehow made it onto the list. A lot of the criteria it looks to me like from afar is just name recognition. So if it’s a big household name, then that puts them pretty close to the top. But then if you’re not on the list in Asia issuing CLOs is a much harder business because your initial cost of capital is higher, and that means less equity distributions over time. So A CLO management firm might say, Hey, I didn’t get a good debt print for the CLO O, but I’ll cut my management fee or I’ll do something else for you. But the good debt execution really puts the top quartile of managers significantly ahead of anybody else who’s in the business or trying to enter the business.

Ted: When the manager goes to the market to create one these, how do they address the buying market beyond what say that most senior tranch is coming from Asia?

Shiloh: So to form a CLO, really the first thing you need is a CLO equity investor like myself. So without the equity, there’s really not much that can be done. Maybe the manager can put up the equity themselves. Sometimes it’s going to be part of the CLOs permanent financing. Other times it’s maybe a bridge until they locate a third party CLO equity investor like myself. But once you have the equity, then you can set up what’s called the CLO warehouse, and that’s used to acquire loans prior to the formation of the CLO. And then you start marketing the CLOs debt. So the AA then is the most important, and then the other CLO securities, the ones rated AA down to double B, those are important, but less so the AAA is 65% of your funding costs, so you need to get good debt execution there. And then later in the process, the other tranches get filled out. So each CLO has a CLO arranger. They have a team that puts together an indenture which has the rules that the CLO is going to follow, and that negotiates economics with people up and down the CLO capital stack.

Ted: So when you’re looking at the CLO equity and you want to know that they have that attractive debt financing, it sounds like there’s a chicken and egg. If you’re supplying the equity before you know what the terms of the debt will be, how do you resolve that in your research?

Shiloh: The equity needs to be first, but the AAA is probably on deck and there’s probably already been a number of conversations there. So that’s part of it. But another thing is that in my market, it’s very transparent as to which managers are getting the best debt execution. A CO manager might come to me and just say, Hey, I print the tightest AAA in the market. I did it last month and three months before that and I was talking to a Japanese bank, and they seem pretty interested. And so that gets the conversation going. But the other part of this is once you have the equity, you’re in a CLO warehouse and you’re buying loans prior to the formation of the CLO, you have three to six months to figure out the full commitment on the aaa. So if it comes back maybe wider than you might like as an equity investor, you can always just stay in the warehouse and just wait for a better time or better execution.

Ted: What does the universe of the initial equity providers,

Shiloh: So I think there’s about 15 of us. One of the common jokes in the CLO industry is that you go to CLO conferences, of which there’s many, and it’s a common theme that, oh, there’s new investors coming into the market and you kind of always hear this, but really I see the same 15 guys. We are often sharing in the same deals, we’re speaking at conferences together. It is a niche asset class, although it’s grown to be a trillion and it’s just a little bit more complicated than owning a high yield bond directly or a s and p 500 stock or a mutual fund. So it does take a little bit of learning to get up the curve. I think for people who spend the time, I think the risk adjusted returns are very favorable.

Ted: So when you are discussing the value of CLO equity relative to other alternatives of someone who’s looking for a certain type of risk return profile, how do you compare it to the other ways people might get exposure to credit markets?

Shiloh: Great question. So if we’re comparing private credit owned predominantly unlevered, a lot of times you’re going to get in a CLO exposure to the same underlying loans. But the difference is in the CLO, we’re employing this long-term attractive funding cost that comes along with the CLO vehicle. So if you own traded the loans they might pay today, call it a yield of around 9%. So if you’re in an unlevered fund, that’s the yield. Then what investors would get would be less management fees and some loan losses. Now if you’re investing in CLOs, the CLO O comes with attached leverage to it. So it might be the same underlying pool of loans, but you have seven to nine times leverage associated with that. So that’s the leverage that would be similar to US Bank today. So in my business, whenever you see a diversified pool of loans, usually somebody is financing against it.

Shiloh: And the reason is that banks and insurance companies and CO AA investors will give you such attractive financing against a diversified pool of loans. They usually people take it. So it’s that leverage in the CLO that bridges you from the unlevered return to the levered one. And we think for an investor that can have a little bit more volatility on their nav, that at the end of the day doing it with leverage is probably the best way to do it. I think the attraction of CLO equity is that the returns that we’re expecting to earn should pretty much rival what we think you get from the s and p 500, but we also think that you can get the returns with a lot less risk. So somebody putting together a diverse portfolio of assets would find CLO equity can push out their efficient frontier or just have a portfolio with better returns and lower risk.

Shiloh: So I think that’s the selling point for CLO equity is that the distribution of returns around what I’m targeting should be I think a pretty tight distribution. So if you invest in CLO equity, you’re never going to triple your money unless you’re buying something very distressed in a real severe downturn. But at the same time, the probability that you have a negative IRR is extremely low. So by our math, it’s about 6% of CLOs that have had negative IRR. So it’s for somebody who wants to be in the mid to high teens and then not have as much downside risk as they might if they just own individual stock, I think it’s a compelling opportunity for them.

Ted: I’d love to dive into how you go about implementing the investment strategy. How do you start to filter what you’d like to have in your portfolios?

Shiloh: So if you want to buy a CLO equity tranche, your options really are to do it in the primary market where CLOs are being created or you can buy CLOs in the secondary market. So broker dealers, they make markets in these securities. The securities also trade in auction processes. So for example, the seller of CLO equity might put out a notice to the market that says, Hey, in two days I’m going to sell these three securities and I’m looking for the best bids. And people put in bids through broker dealers for that. So the first thing that you need to decide is just where you’re seeing more interesting opportunities for the primary or the secondary market. So what we do is we basically have a tracking sheet which has every CLO opportunity that we’ve ever been shown in it. And the first screen is just, well, you buy A CLO equity tranche very simply, you put in the price and you put in your 2% expected default rate on the loans, and then you’re screening highest to lowest return opportunity.

Shiloh: But it’s much more complicated than that. So if the CLO equity has a higher return associated with it, then you need to delve in and be like, okay, well what’s the reason? And sometimes it’s reasons that are good and that are going to lead to pursue the opportunity, and then other times it’s just not going to be an opportunity that you want to chase. Great reasons to get a high IRR would be I’m buying at a good price, I have good debt execution out of Asia, the CLO manager is working for a reasonable fee. There’s some deal specific things if the CLO equity offers high returns, but the reason is that the loan pool is very spread, well that means, okay, that’s nice for the equity, but a higher spread loan portfolio could result in higher loan defaults over time. So that’s the opportunity that we would screen out.

Ted: As you’re diving into any one of those opportunities, you’ve got a different capital stack on the right hand side of the balance sheet of the CLO, and then you’ve got say, 200 loans on the left hand side. How do you go about doing your research to determine whether you think it’s an attractive opportunity?

Shiloh: So one of the things that we don’t do is deep dive due diligence on the underlying loans. And the reason for that is a few. So one, there’s going to be 200 or 300 different loans in the portfolio. Usually the max loan size is going to be 1% of a UM or thereabouts. And then if we’re talking about broadly syndicated CLOs, the loans are traded. So you could do due diligence on underlying loan, it’s 50 basis points of the loan portfolio, and then you found out three months later the CLO manager traded it and replace it with another loan. So you’re not really going one by one through loans and asking the CLO manager to explain themselves. So there’s some big picture details that are reported by the CLO that would be of interest. So one is the amount of defaulted assets in there, which usually there are going to be the amount of triple C rated assets, so those are loans that you have much higher risk to default.

Shiloh: And then another metric would be the amount of loans trading below a $90 price. So we usually think of loans that are worth 91 cents or higher as being worth par and loans that likely default at that 2% rate. But if the loan at 80 might not have defaulted yet, it might not even be ccc, but you would never buy a CLO with a loan trading at 80 and not make some kind of adjustment in terms of the price you’d be willing to pay. Another thing that we would shy away from is often there’s very high returns offered for CLO equity securities that are short. So the CLO equity might have an eight year life, and if you want to step into that in the secondary with one year to go or something like that, usually you can buy that at returns that would at least model to be very attractive, but that would be the most risky CLO equity securities you can buy because sooner or later the loans will be liquidated and the CLOs debt gets repaid and the equity gets what’s left. And if you’re only really signing up for that last part of the CLO O or you’re not getting a lot of distributions along the way and you’re just interested in the outcome of a liquidation, that’s not a trade that would work for us.

Ted: Along that type of example, how do you think about the active management component by the CLL manager?

Shiloh: So I think active management is very important. You’re paying them 40 basis points on average, and for that, you’re not just getting somebody who’s picked an initial portfolio of loans and then just let us sit there. The CLO managers, the good ones, they’re actively trading their portfolio in the loan market. How that works is, for example, if JP Morgan or B of A is underwriting a new leverage loan, they price that in a way to really incentivize buyers of the loan to come in in the primary transaction. So a new loan might come at a price of 99 cents on the dollar, but it was underwritten in a way that after it was allocated that it’s worth 99 and a quarter or 99 and a half. Some little bump in economics is what you get by playing in the primary market for loans. So a lot of the time, some successful strategies and leveraged loan management would be to be very active in primary where you’re getting loans that trade up incrementally and over time rotating out of loans that might be more risky or just be more seasoned.

Shiloh: So those are some of the strategies they do, but the amount of churn CLO equity investors are definitely looking for managers with more churn of the loan. So that implies active management. Now, it needs to add alpha. It’s not just rotating in and out, but I think that’s a metric that people in my seat are going to focus on. I think there’s also a qualitative component to this, which is I’ve been investing with the same CLO managers for 10 plus years. So when we’re looking at a new CLO in the primary, you can do so much analysis on the underlying loans and how they performed, but qualitatively you’ve already done a few deals with the guys and you can just pull up the CLO positions that you already own with them. And I think that’s obviously something that you need to wait in your decision process.

Ted: You have what sounds like just a massive data. So all of these CLO managers over 10 years, each CLO having 200 names in it, the performance of all those, how do you process all of that information that’s coming in?

Shiloh: A lot of the big investment banks, they have CLO research teams, they’re analyzing the data as well as we are. So they’ll put out a stat that says something like, Hey, in the last year, these are the top 15 managers who have grown the par balance of their loans. Or another bank might say, Hey, these are the managers who reduce their triple C loan exposure. And when you look at that is one of the challenges in evaluating A CLO managers that there’s so many different metrics that you could choose. I could list a dozen of them. At the end of the day, what it really adds up to is what I care about and what our investors care about is the IRR of their deals. But pretty much every market participant I think uses software called intex, which models CLOs very quickly. You can pull up your portfolio and see how it compares to the other CLOs out there. There’s this qualitative element once you’re having a good experience with a CLO manager, it probably would be hard for a newer CLO team to wiggle themselves into the list of people that you’re looking to work with.

Ted: How do you think about putting together your portfolios of CLO equity and debt securities?

Shiloh: So the 90% of the CLO market is broadly syndicated CLOs. So if you look in there, you’re going to find companies who borrow a billion dollars and up basically. And so our focus though at Fire Rock is really middle market CLOs where your typical borrower is going to be 200 to 400 million of revenue. It’s not going to be a company that you’re going to read about in the Wall Street Journal or anything like that, but still going to be a business that provides material product and service in the economy. So what we found is that portfolios of middle market loans, they both pay higher rates to the lender lender, but they also have more favorable loss statistics over time. And on top of that, middle market loans tend to be much less volatile than broadly syndicated loans. And as a result of that, the volatility that you see on middle market, CLO double Bs and middle market CLO equity is just going to be more favorable to that of what you see in the broadly syndicated CLO market. And so that’s where we’re focused is roughly this 10% of the market niche and in this part of the market, instead of there being a hundred managers, there’s about 15 or so that work working with. In a typical year,

Ted: When you build a portfolio, what does it look like in terms of the number of positions or line items that you’ll have

Shiloh: To be diversified in the CLO market? I would say it’s something like having max positions of around 5% of the portfolio. Each CLO again is going to have 200 or 300 different loans in it. You would not need a hundred CLO equity tranches to be diversified. And then two, a lot of the CLOs are going to own similar loans. So for example, Asurion is the largest loan in CLOs today. They do contracts for iPhone and Samsung phones. The insurance contracts, if you go out and buy ACL O, you’ll probably find them in there. I think having call it 20 different CLO equity tranches would result in a pretty diversified portfolio. The one thing you want to be diversified though is just the life of the CLO. So in a diversified CLO fund, you wouldn’t want to own 20 CLO equity tranches all bought in 2021.

Shiloh: We’d want the CLOs bought at different times. And that’s important because the CLO starts its life with a two year no-call period during which the rate on the AAA down to double B, it’s all fixed and you can’t really monkey around with it. But after the two year no-call period comes off. If it’s to the advantage of the equity, you can go into the market and refinance the CLOs debt at lower rates. You can extend the life of the CLO or you can decide to call the CLO O and that’s just liquidating all the loans and getting your money back.

Ted: When you own this portfolio of the 20 CLO equity pieces and you’re getting distributions along the way, what are the structures that you put together look like that you offer to investors that can match the right liquidity that you’d need to optimize how you want to manage this portfolio with the experience of your investors? On the other side,

Shiloh: What we do at Flatrock is we have three different interval funds. They work similar to a mutual fund, so people can buy them with the ticker through an RAA. Actually they’re not available just to the public. Contrast to a mutual fund is that the securities we’re investing in are pretty illiquid. So we’re not in a position to give anybody daily liquidity if they want out. So what we can do is have these 5% quarterly tender periods where people want to tender their shares to us, the fund will buy them back. So this is a great structure I think for CLO equity because the CLO equity does pay these high cash distributions quarterly. So a common question I get asked from our investors is, well, if you’re tendering for 5% of shares, where does the cash come from? And the first answer is, well, the CLO equity pays very high cash distribution. So you have that on hand and then backup answers would be, yes, I also have a line of credit from a bank or I can just borrow or there’s cash on the balance sheet. The interval fund structure is one where I see it taking market share over time. One of our three funds was initially a private BBC, and we converted that into an interval fund because we believe so much in the structure. And then if you’re an investor in an interval fund, it’s the same SEC reporting is mutual fund.

Ted: What are the advantages of that structure compared to say A BDC or even just a portfolio of the loans?

Shiloh: If you contrast it to A BDC, I think one of the challenges for BDC investors is on the one hand, the BDC is like a close end fund. The shares trade around all day, so you can get liquidity really at any time. But the BDC can trade at a premium or discount to book. Unfortunately for BDC investors, usually it’s a discount. So an investor in those shares, they have both the volatility of changes in the underlying prices of securities, but on top of that, the volatility of just the difference between where the funds trade in the market versus the underlying nav. So the end result of that is BDCs are wildly volatile and in a period like Covid for example, that downturn a lot of BDCs cut in half. And well, if that can happen from a portfolio of predominantly secured loans that pay a dividend yield of nine or 10%, the risk reward there I think would feel funny to a lot of people. So I think that’s one of the reasons that people would prefer the interval fund over the BDC.

Ted: And how about compared to just a private credit vehicle?

Shiloh: The primary difference is going to be in liquidity. How the 5% tenders work is that if every single investor tendered at the same time, you’d get back 5% of your money, but realistically, only a small percentage of your investors should be tendering. At the same time, if you want to tender your shares, you should get back a lot of your money from these tenders. If you’re in A-G-P-L-P fund, you’re committed to lockup capital seven plus years. I think it’s becoming pretty tricky for a lot of large institutional investors to make commitments that are that long in duration.

Ted: What is your research team look like to implement the strategy?

Shiloh: We have an investment committee, which is three folks, myself, our CEO and our CFO, and then people who are working on the CLO team. There’s three of us, and CLO investing is not similar to the team structure. You might see at a private equity firm or even a private credit firm, for example, CLOs are modeled in software that everybody uses. So to get a good sense of what’s happening, you pull it up and literally in 10 minutes you have a pretty good idea of what you’re looking at and if it’s interesting. So in CLO LO investing, as you become more senior in your career, you don’t start flying over from 10,000 feet and making broad pronouncements about the market or managers. All the details are super relevant. I’ve been doing this 20 plus years and I’m still reading in dentures and modeling CLOs and involved in all the negotiations that go with putting a CLO together to contrast it with loans.

Shiloh: For example, if you buy a first lien loan with a 40% loan to value, and for some reason there is an error in the model, at the end of the day, you still land at 40% loan to value and you’re probably getting your money back. CLOs and CLO equity in particular, that’s not the case. So CLOs are going to produce a stream of cash flows over time, and then there’s one payment at the end when the CLO is liquidated and people get whatever cash remains, there’s no par payout at the end. A lot of times you’re getting back 40 cents, 50 cents on the dollar. Now over the eight year life of the CLO, you’ve got these very large distributions along the way. Hopefully it nets to a nice return for you, but you don’t get far back at the end. So the modeling of it really needs to be a hundred percent accurate because every dollar is going to be part of that IRR. There’s no magical a hundred cents that comes back to you at the end.

Ted: What does happen at the end as the manager is unwinding the CLO?

Shiloh: So the typical CO is going to have a five-year reinvestment period. And during that time, loans are constantly prepaying at par. The CLO managers going out into the market and they’re buying new loans with the proceeds. Then after the reinvestment period ends, for the most part, that stops. So when a loan prepays at par, instead of buying a new loan, that cash is used to repay at the AAA security first. Then when that’s fully retired down to the aa, so after the reinvestment period ends, the CO is losing its most attractive financing cost. So the CLO equity distributions are declining. Whoever owns 50% or more of the CLO, when they decide that they’ve delivered enough and want their money back, they can notify the CLO manager and tell them to put all the loans out for sale. So the thinking once you get past the end of their reinvestment period, for somebody like me, there’s a few variables that would determine how long the CLO should go.

Shiloh: So one is if you’ve got a really good financing cost, aaa, even if you’re losing it partially over time, it may make sense to just keep it. And then the other function in there would be the liquidation value to the equity. So if for example, we’re in a period where loans have traded down, then there might not be a high liquidation value for the equity. And in that case, you’re not incentive to call a deal if you’re an investor in double bbs, you’re basically trying to figure out what the equity might do. So a lot of the bbs we buy are later in their life and we buy double Bs at discounts to par almost all the time. So the quicker you can get repaid, the better. So when we’re buying double B securities, we’re figuring out, hey, which of these CLOs are interesting call candidates? Which ones would we call if we were the equity? And that’s part of our decision making and how we filter out the double Bs that we buy.

Ted: If you look at the drivers of your return over time, how much of it is the year over year yield that accrues down to the double equity and how much of it comes from the unwinding of the portfolio?

Shiloh: So one of the things that’s interesting about CLOs is that I mentioned they have this two year no-call period on them in which you can’t really tinker with your AAA and double B or what they are. But after that, what we hope to do with a lot of our CLOs is really have them as permanent capital vehicles. So I mentioned that the reinvestment period might be five years, but if you go out five years and the CLO has performed well, your incentive to just try to go back into the market and extend the CLO O’S life and add another five year reinvestment period to it. So by doing that, you skip two to three years of potential de-leveraging and receiving lower cash flows. Instead of having that period, you just stay fully invested and keep going. So a transaction like that would be very accretive for the equity.

Ted: What are some of the other nuances of how you can drive returns for your investors through the structures?

Shiloh: Let me give you an example of some of the upside that I think exists in these deals that we try to take advantage of as an equity investor. So I mentioned there’s refis, there’s CLO life extensions every quarter after the reinvestment period ends, the CLO equity investors looking to maximize their returns. It may be the case that a call one year after the reinvestment period is the ideal one for the equity and it could go as long as four years. So that’s some other upside that comes to us. I think another source of potential outperformance for equity fund, something that I’ve done and I think our competitors have done to some extent as well, is that if I rewind the clock to the spring of 2020 CLO securities are trading at really discounted levels. So if you’re an investor in CLO equity, you don’t have a crystal ball for how quickly the economies going to recover.

Shiloh: So equity feels a little bit scary, especially when some of the underlying businesses in the CLO aren’t even open for business. That’s obviously not good. But at the same time, what we did is we looked at CLO double B notes that were trading in the market in the sixties, seventies, and eighties. And in looking at those, you just ask yourself, okay, well what percentage of the underlying loans would have to default such that I’m not money good on this double B? And even during covid, we saw double BS as securities that we expected to be really rock solid. So we are a CLO equity fund, and I put equity in quotes now because after COVID started, we were buying double Bs. We felt like, hey, you can get equity-like returns here or better and be more senior and de-risk yourself. Why wouldn’t you do that? So a lot of times people who are investors in CLO equity are looking to the double B as a potential alternative. And when those are trading at discounts, that can be a pretty compelling place to look for a turn rather than your more traditional trade.

Ted: So you’ve experienced an incredible growth in the industry you’re participating in for a long time. What do you think happens from here over the next five or 10 years in this part of the market?

Shiloh: I think the market continues to grow probably at a mid single digit clip. I think that we talked earlier about drivers being people wanting exposure to first lien loans, the performance of CLO securities over time. And I think it’s partially just an education process. So when we’re marketing our funds to investors, a lot of the times they’re not familiar with private credit, they’re not familiar with CLOs or even traded loans. There’s a lot of education. I think that’s what’s being done. SOFR is a little bit less than 5.5% today. If you’re lending, again, 4% above that, people are going to find that to be a pretty attractive yield that I think is just going to pull more and more people into the space.

Ted: Closing before your hobby or activity outside of family,

Shiloh: Almost every night I go to the jiujitsu studio and train that with the guys. What I really like about it is it’s both a mental challenge and also physically exhausting. There’s the comradery of training with the same team every day. But the other part of it is that in Jiujitsu, you are 100% present. You’re just really in the moment trying to deal with the immediate problems. And it also teaches you how to learn and acquire new skills and really think about the best way for you to learn new movements and tricks. I find it to be really enjoyable.

Ted: What’s one fact you find interesting that most people dunno about you?

Shiloh: So once I started working, I did two years on the sell side and then transitioned, I think I worked for six years on the buy side in Los Angeles. And then after that, that would’ve been a time where a lot of people in my position would’ve maybe gone back to school and gotten an MBA. But I had already done the CFA and I had a master’s in public policy where there would’ve been some overlap with an MBA. So what I decided to do is I took a sabbatical and traveled the world for two years. So I visited over 20 countries, learned Spanish, I learned Portuguese, I still speak Spanish, Portuguese is gone. Unfortunately, I also did a lot of surfing. So I’m from a lower middle class family, and we didn’t have the opportunity to take a lot of vacations when I was younger, and I took that two years to see the world and really enjoy life.

Ted: What’d you learn most from that experience?

Shiloh: One of the standout experiences for me was living in Rio where a lot of people are living in favelas or slums and they’re living on maybe $5 a day or something or less. But when you meet these people, when you spend time with them, they’re some of the happiest people in the world. They’ve got the Brazilian flag painted inside their home, they’re playing soccer on the beach, they’re swimming in the ocean. And if you compare that to a lot of guys who might have a corner office on Wall Street, the contrast is just so stark, and I think it just shows you the value of being fulfilled or being happy with what you have and thinking about ways to live your life in a way that you can get that enjoyment and satisfaction.

Ted: What’s your biggest pet peeve?

Shiloh: My biggest pet peeve at work at least, is where people reach out to you trying to sell you something, but don’t really have anything that they’re offering back. So let me give you the example from the perspective of how we do fundraising. One way would be to call a bunch of RAs and family offices and say, Hey, we want you to invest in our fund. Okay, we want that. Why should they want that? The better way to do it is to offer something instead of to ask. So what we offer is education, education on private credit, on CLOs. We have the clo o investing book that I wrote and other resources. So we’re reaching out to people. We want something, but we have something to offer. And I think it’s important that people try to think about framing what they want in a way where maybe something’s coming back to the other person.

Ted: Which two people have had the biggest impact on your professional life?

Shiloh: So I think the two biggest people are going to be the two people in HR who took an Excel spreadsheet with a hundred names on it of people from different universities and decided which industries they were going to cover. So I think we like to go through life thinking. We’re in charge of everything that’s happening to us, what’s happening around us as a result of our hard work or lack thereof or of the smart calculated risks that we’re taking. But in reality, there’s a lot of random things that affect our life in huge ways and assigning me to the financial institutions group, that’s what resulted in us chatting here today. It could be in another universe. I could have been in the telecom group and who knows where I’d be. Unfortunately, I’m pretty happy with how it worked out.

Ted: What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

Shiloh: So one of the things that I do, and one of the things I think we try to do as a firm is to take the most generous interpretation of what’s happening in a situation where you feel like you’re not being treated well or you don’t like what the other person’s doing. Instead of jumping to the conclusion, oh, assigning the worst motivations to the person, instead really assigning the best. Somebody shows up late to a zoom call. The worst impression would be, okay, this is somebody who’s not motivated or didn’t care or didn’t prioritize this, and the best is, Hey, you just don’t know what other people have going on in their life. I make an effort daily to go with the generous one. And start with that.

Ted: What life lesson have you learned that you wish you knew a lot earlier in life?

Shiloh: I found that I really like learning. So I have three different master’s degrees. I studied public policy at one point, financial mathematics and statistics, and then after graduate school, instead of learning in the academic environment where you’re really spoonfed information to try to learn things as an adult. So just like I go to the gym multiple times a week and I’m working out whatever muscle group, I try to treat my brain the same way. So I’m constantly learning new things. So piano, I mentioned jujitsu. I try to stay current with Spanish and just always finding mental challenges. I think that’s, at least for me, it’s a key to feeling good during the day, and I think it might keep you a little younger as well.

Ted: Shiloh, thanks so much for sharing this incredible education on CLO investing.

Shiloh: Thanks for having me, Ted. That’s great.

Ted: Thanks for listening to this sponsored Insight. Sponsored episodes are paid opportunities for another 12 managers a year to appear on the podcast. If you’re interested in telling your story in front of the largest audience of investors in the industry, please email us at team@capitalallocators.com to apply for one of the slots.