Shiloh:

Hi,

I’m Shiloh Bates and welcome to the CLO Investor podcast. CLO stands for

collateralized loan obligations, which are securities backed by pools of

leveraged loans. In this podcast, we discuss current news in the CLO industry,

and I interview key market players. Today I’m speaking with Allan Schmitt, the Head CLO Banker at Wells Fargo. Allan has structured many of the CLOs I’ve invested in, and at my prior firm, Allan was part of the team that provided our business development company, an asset-based lending facility, or ABL, and ABL is just leveraged against a pool of leveraged loans. As you’ll hear during the podcast, Wells is active both in lending against diversified portfolios of loans and arranging their securitizations through the CLO market. I asked Allan to come on the podcast to discuss rated feeders, which are a new flavor of CLO that is growing in popularity. If you’re enjoying the podcast, please remember to Share, Like, and Follow. And now my conversation with Allan Schmidt. Allan, welcome to the podcast.

Allan:

Thanks, Shiloh. Excited to be here.

Shiloh:

Is it a pretty slow August on the CLO banking desk?

Allan:

I think most people might wish it was, but it’s definitely

been an interesting summer across the board. I think we’ve seen, obviously with

CLO spreads tightening, really across the balance of the year, has created

really an overwhelming number of reset and refinance transactions for the

market. So not only Wells, but across the board, you’re seeing 10, 15 deals a

week come across the transom. So I think everywhere from the investor side, as

I’m sure you’re aware, to the underwriter side, to the manager side, to the

lawyers, the rating agencies, I think everyone is really working through the

screws to get transactions through the pipelines here in August. So…

Shiloh:

It definitely seems that way. We’ve known each other for

quite some time. And maybe you could tell our listeners a little bit about your

background and how somebody becomes a CLO banker.

Allan:

Sure. So I’ve fortunately been in the industry around CLOs

my entire career, which dates back to 2006. So started right before the global

financial crisis. Certainly as an analyst at that time, it was an interesting

period to really begin to get involved in the market and certainly had a front

row seat to a lot of the activity that was happening at that time. My entire

career has been with Wells and predecessor firms, so I’ve been fortunate from

that perspective and as we moved out of the global financial crisis, was able

to be really on the front lines as well as we built the business at Wells

around private credit lending, around CLOs, and really was instrumental in

terms of growing my knowledge base, growing both internal and external

relationships during that period. So obviously where I sit today in my current

role, lead both our CLO effort across both broadly syndicated and middle market

CLOs as well as our private credit lending business there. And as we’ll talk

about more recently expanded our offering underrated feeders as just an adjunct

to what we’re able to do for our private credit clients. So obviously a

longstanding period of time here in CLOs, but excited about it.

Shiloh:

So what are some of the key character traits of somebody

who’s successful in CLO banking?

Allan:

So I think it’s a number of things. I think first and

foremost it’s being a relationship manager, so someone that’s communicative

both to internal counterparties, but even more importantly to clients and

investors like yourself, folks that have the ability to think dynamically on

their feet. CLOs are not an overly complex structure, but they do require the

ability to put pieces together both from a structure perspective but also the

different constituents, both equity manager investors. And so being able to

play that process effectively and walk out of transactions where everybody

feels it was successful I think is a key piece. So someone who can manage that

process and communicate effectively is critical and certainly is depending on

where we’re hiring people as folks move up the ladder, really being able to

develop and institutionalize a lot of the client relationships that we have in

the market.

Shiloh:

And then for the junior people you hire, are they spending

a lot of their time doing financial models? So accuracy is the key

differentiator there?

Allan:

Yeah, I think attention to detail, right, to your point,

and being able to both be intellectual around structure, documentation, et

cetera is obviously critical. Obviously it’s a learning curve that folks have

and folks get into, but someone that has that ability to grasp both the legal

and structural aspects of the business quickly, and obviously having that

strong attention to detail, is obviously important as well.

Shiloh:

And so as you become more senior in the CLO business, is

somebody like you still in the weeds with the modeling or are you reviewing at

a high level the work that’s done by others?

Allan:

I spend a lot of my time, I think on the client

development side of things, the more strategic side, whether that’s when we’re

bringing a CLO transaction, helping to formulate the distribution process, the

distribution strategy, certainly on the structuring side as well, helping to

provide ideas and thoughts around different structural nuances or things we can

focus on within specific transactions. So while not in the weeds punching

numbers necessarily, certainly maintaining a pulse on what’s happening in the

market and how we can create better structures for our clients to optimize from

an ultimate execution perspective.

Shiloh:

So I think there’s around 15 or so different CLO banks out

there. How is Wells differentiated from some of the others?

Allan:

There’s certainly a lot of players in the market around

syndicated CLOs and even becoming more around middle market CLOs. I think from

our seat, we try to differentiate ourselves a couple ways. One, I alluded to

the bAllance sheet that Wells provides into the private credit space, and I

think that has an extension into the broad syndicated market as well. And it’s

not just about providing bAllance sheet, but it’s providing that capital in a

way that is beneficial to client and can help drive business for the platform

holistically. But it’s also around providing bAllance sheet on a consistent

basis. I think what I mean by that is our approach to lending over the course

of the last 15 to 20 years has not changed materially. I think we’ve always

been an active participant or a leading participant in the private credit

space. So our clients have confidence, have an understanding in terms of how we

approach the market.

So that consistency, we obviously want to adapt and evolve

as the market evolves, but our ability to maintain consistency across different

markets, whether it’s volatility, as we saw earlier this week or what have you,

we’re able to consistently provide that capital to clients both in a strategic

and customizable way. I think the other is, it sounds simple, but from a

customer service perspective, the relationship management perspective, our

ability to help clients on the financing side for a lot of their funds from

start to finish is critically important. When we think about a lot of the funds

that have been raised, they need multiple forms of financing, whether that’s

traditional ABL financing, CLO financing.

Shiloh:

An ABL is an asset backed loan.

Allan:

That’s right. Wells is providing the senior financing on a

pool of loans, so substituting a CLO, AAA, AA for a bank, ABL financing.

Shiloh:

So there the point you’re making is that Wells actually

likes to lend against these loans, so you’re going to require some third party

equity obviously, but maybe before there’s ACL O, there’s a warehouse set up

where somebody again puts up some equity and wells starts advancing the debt

there and maybe there’s a CLO takeout at some point or maybe there’s not. And

either way, Wells likes to take the senior risk, if you will, against a pool of

senior secured loans. Is that how to think about it?

Allan:

That’s exactly right. When we think about our client base,

a lot of the financing to private credit is not necessarily in CLOs, it’s in

that ABL structure or that bank financing structure. And so we’re able, and we

like that product, we like that lending, its core to what we do as a business

and a platform. So we’re able to provide that to clients, but we’re also able

to facilitate and think about strategically the execution of CLOs for clients

as well. So all of that from a relationship management perspective, all of that

sits within our team. So we have the ability to really provide clients with

ideas and thoughts around the best form of financing for their funds.

Shiloh:

At a previous firm, as you know, I was the counterparty to

a Wells line of credit where Wells was lending against a diversified portfolio

of middle market loans, and I think generally an advance rate of 65 or 70%. Do

you have any sense for why it is that that business works for a bank like Wells

and other firms may not find that business to be as appealing?

Allan:

I think it’s interesting. I think we’ve seen other

institutions I’d say come around or become more active and engaged in that

senior lending there. So I think when your question on how does Wells

differentiate, we differentiate because we have consistency and a long-term

process around that business. But I think other banks and institutions are

active in it, are growing in it, and it’s becoming a more competitive space

there.

Shiloh:

So one of the things I’ve noticed in the CLO equity trade

is that before the CLO begins its life, often there’s this warehouse period

where some equity is contributed and loans are acquired using leverage from a

bank and at other banks, that warehouse is really something they’re providing,

really they want it to be as short as possible. They don’t really like the

risk, they want you to be in a warehouse for a couple months, then they’re

ready to do a CLO and then they earn a fee, the bank does. And then there’s no

real exposure to the CLO after that. In some of the warehouses I’ve done with

you guys in the past, the vibe is you put up equity, Wells like lending against

the loans as a senior lender, and we can do a CLO takeout soon or later or

maybe never. And it seems you guys are fine with that, which I think is

different from some of the other shops.

Allan:

I think it certainly obviously depends on the situation

and the structure of the motivation, if you will, of that vehicle at the

outset. But to your point, we are able to be patient. Again, we approach it

very much from a client relationship type perspective and want to find the best

takeout and the best long-term structure for the client. I think we certainly

want to do CLOs, we certainly want to earn fees on the backend, but in certain

structures we’re not here to force the takeout and want to develop partnerships

for the long-term. And I think we’ve done that over the years and you can see

that obviously in some of the repeat managers that we partner with, but

definitely take a longer term view of that warehouse to take out than some

others.

Shiloh:

So then in the CLO market, the three biggest categories

for CLOs would be European versus US, and then, in the US, and by the way, we

don’t do anything in Europe. And then domestically it’s broadly syndicated CLOs

and middle market are the big two. Could you maybe just compare and contrast a

little bit the structural differences between the two and then from there maybe

we could build into the rated feeders as well?

Allan:

Definitely, and I think when you think about those two

markets, probably syndicated and middle market CLOs, at this point, there’s not

a lot of structural differences between them. You certainly have similar rated

notes, you have similar reinvestment periods. BSL might be five years, middle

market might be four years, albeit there are middle market CLOs now getting

done with five years. I think the bigger difference really when you think about

the two markets is the underlying motivations for transactions. So middle

market CLOs are used typically by managers in most senses as financing vehicles

for larger fund complexes. We talked about the ABL business that Wells does and

others do, which is a big form of financing for these larger fund structures.

And CLOs are another form of financing. So where broadly syndicated CLOs are

going to be much more of a true arbitrage structure, where the manager is

partnering with equity and are going out and buying loans in the secondary

market, buying loans in the primary market from large institutional banks. The

middle market is much more of a longer term financing vehicle where they’re

originating assets on a direct basis over a long period of time and turning

those assets out. So the motivation that you see between the two is probably

the biggest difference there.

Shiloh:

So in your terminology, an arbitrage CLO is one where

there’s a third party equity investor who’s signing up, likes the risk return

profile of the investment, and that’s who the end investor is there. And then

for middle market, a lot of times it’s a financing trade. So by that there may

be a BDC or a GPLP fund with a diversified portfolio of loans and it’s

advantageous to them to seek leverage against that because it’s long-term

leverage done at attractive rates and that enables the BDC or GPLP fund to increase

their return on equity. But in a structure like that, the equity is owned a

hundred percent by the BDC or the fund. There’s no third party equity, there’s

no Flat Rocks involved in that case.

Allan:

That’s right, and I think that’s also when you think about

one of the bigger differences between the two BSL and middle market CLOs, BSL

is typically always going to issue down through double B rated notes or all the

way through equity and middle market Cs because of that financing structure for

BDC or a fund, they may only issue down through AA or single A because the

leverage profile of those vehicles or how much leverage those vehicles are able

to run is meaningfully less. So that’s why a lot of times you won’t see

mezzanine or non-investment grade tranches issued for middle market CLOs.

Shiloh:

So the broadly syndicated CLO might be levered, was it 10

times on average, where the middle market might be leveraged seven and a half

times. So less leverage there. And then the CCC basket is another big

differentiator. In broadly syndicated, you get a seven a half percent triple

CCC bucket. In middle market, you get 17 point a half on average. Of course

there are some differences in deals and that gives the manager more flexibility

because the middle market loans tend to not be as favorably rated by Moody’s or

S & P. And then you pointed out the middle market CLO might have a four

year reinvestment period, so a little shorter than the five years you get in

broadly syndicated. I think those are the key differences. Another minor one

would just be reinvesting after the reinvestment period ends. So in broadly

syndicated CLOs, whenever you get unscheduled principal proceeds, whenever

those come back to you, which is most loan repayments are unscheduled anyways,

then a lot of times you can reinvest that, subject to some constraints in the

deals. Whereas for middle market, actually the reinvestment period ends. It’s

very simple. There’s no more reinvesting. It sounds like a subtle difference,

but I think it does actually matter in terms of how long the deal will be

outstanding for and it matters for equity returns. I think. If you think about

the aaa, which is the biggest financing cost and broadly syndicated, the loan

to value through AAA is going to be about 65% would you say, or

Allan:

62 to 65%

Shiloh:

62 to 65. And then for middle market it’s going to be

Allan:

55 to 58.

Shiloh:

So it sounds like you get a lot more equity or juniorcapital in the middle market. And then in terms of your banking team, you havea middle market team and a broadly syndicated team, or these are similarproducts and everybody works on the different deals?

Allan:

As we’ve talked about, there’s similar enough products where we generically have everybody working on similar deals. We do have some senior members of the team more from a relationship perspective that are specialized in either BSL or middle market as they think about developing client relationships and whatnot. But from a structuring deal execution

perspective, we view there to be enough similarities between the products and certainly from an investor perspective as we think about distribution of the products, that there’s enough similarity where the same individuals are able to function there.

Shiloh:

And then one of the reasons I wanted to have you on the podcast this week was just to talk about rated feeders a little bit. So that’s a new flavor of CLO in the market. What are the basics of a rated feeder?

Allan:

So a rated feeder is a structured credit vehicle where, as opposed to being secured by underlying assets directly, as a CLO would, you’re secured by the LP interest of a private credit fund. And that private credit fund can really be of any type. It can be direct lending, it can be asset-based lending. It can be all sorts of different types of private credit assets, but for the most part, most of them have been done off of middle market direct lending assets. The structure has been utilized for many years. As you think about insurance companies who want to make investments in private credit funds, they’re able to do so through a rated feeder structure in a more capital-efficient way. So again, the underlying asset that is getting levered or is getting tranched out is an LP interest of a private credit fund. So when you think about that GPLP structure, LP fund where you have multiple different institutional investors making LP commitments, some of them might be insurance companies that want to gain access to that fund.

So for them to do that through a rated feeder structure, they’re able to do so in a more capital efficient way. And the reason for that is the leverage profile of a lot of these funds, as we talked about earlier, is only one or two times leverage. So they’re run at fairly low leverage points. And so while the rating agencies are able to get comfortable by tranching out that LP interest and adding incremental rating levels to that for any investor, but predominantly insurance companies to receive incremental capital efficiency there. So historically to this point or to recently, insurance companies have bought vertical strips as we call them, buying a AA, single A, triple B in equity of that rated feeder. And so they’re buying the entire portion for that capital efficiency. But most recently we’ve really thought about that structure on a more horizontal basis, which is more akin to middle market CLOs where we’re using that same radium methodology that insurance have used in trying that out, but selling that to different investors at different risk return profiles there. So instead of one investor buying it all, we might be selling AA, single A to different investors.

Shiloh:

So I think the structural setup here is, imagine your rated feeder, let’s call it 300 million, and let’s say the underlying fund is BDC just to make it simple. Then the rated feeder takes the 300 million that it raises from third parties, it injects that into the BDC, and the BDC over time will pay dividends up to the rated feeder in the dividends on the 300 million that arrived at the BDC. But in the rated feeder structure, as those dividends get passed up to their rated feeder, instead of having all the dividends just paid out rata to the 300 million of equity, instead the setup is the tranching that you mentioned, where first there’s a AAA or AA or whatever it is, they have the first priority on the dividends from the BDC down the line, and then there’s an equity investor and the rated feeder as well, and they’re the person who gets paid whatever remains.

So again, the total income into the rated feeder is the distribution from the BDC, and it just split up, senior to junior, with equity taking the remainder. One of the reasons these exist, I think to your point, is that if you’re an insurance company, you’re basically investing 300 million into the BDC. So the insurance company can either end up with a $300 million limited partnership agreement or LP investment in a BDC, or they can end up with 300 million of investments in a series of securities rated AAA or AA, whatever it is down the line to double B, and they’ll get just much more favorable regulatory treatment for that. So if you’re an insurance company, you don’t want to own a lot of equity, you want to own as many senior rated securities as you can.

Allan:

That’s exactly right. When you think about the rated feeder, especially to your point on the waterfall and how cash is distributed, it doesn’t look that dissimilar than any other structured vehicle where cash is being distributed down through the priority of payments or through the different ratings to the equity at the bottom. I think the difference obviously is there’s effectively one asset. So one LP interest to the fund is distributing that cash into the vehicle that’s getting distributed versus a CLO that might have a hundred unique assets where the cash is coming in. So the investors are really one step removed from the assets than they would be in a middle market CLO. But you have as an lp, as the rated feeder acts as an individual LP of the fund, it has the same rights that any other LP would have in terms of access to the assets.

Shiloh:

So then I understand the rationale for why an insurance company would want to use this structure, but are you also seeing interest from other investors that don’t have regulatory capital that would care about a Moody’s or an S & P rating?

Allan:

Certainly. So obviously the insurance company has been the predominant of the product there, but we have seen an expansion of that beyond insurance companies, not so much as to where they’re focused on capital charge

treatment, but investors are more focused on where they can find increased

spread or increased return really within the same asset class. So the ability

for banks or asset managers or hedge funds or different CLO investors, the

ability for them to buy a more structured complex vehicle is going to come with it a higher spread or a higher return. So we have seen a lot of investors,

we’ve seen spread compression across markets, look at rated feeder notes and look at these structures as another way to really gain access to the asset

class where there’s the ability to garner incremental spread through that level

of complexity through that level of illiquidity there. So we’ve obviously done

a few of these to date and have probably seen the investor base on each

subsequent one continue to grow and broaden and are seeing broad interests and growth there.

Shiloh:

So the most senior securities that are issued by the rated feeder, are they actually rated AAA or is it more of AA, single A, because you are, as you said, one step removed from the assets?

Allan:

So the most senior tranche in rated feeders is really AA. Most of them are either that single A or AA is the most senior rating. It’s certainly because of the one step removed from the assets. The other piece is the fund that sits above the rated feeder is also running leverage. So there’s leverage at that fund level, usually in the form of a bank ABL as we talked about. It could be in the form of CLO tranche, it could be in some other unsecured debt tranche, but there is some form of leverage typically at the fund level that sits above the rated feeder. So that’s another reason why obviously, from a rated entity perspective, they factor that fund level leverage into the rating as well.

Shiloh:

So then let’s just compare for a second, owning the AA of middle market CLO versus the AA of the rated feeder. So in the rated feeder, you do have this ABL sitting at the fund or the BDC level that has first priority or that’s in the first security position. If you’re sitting at the rated feeder, all the management fees and incentive fees that are paid to the manager of the BDC, those are taken out before any distributions are sent up to the rated feeder. So essentially those become senior to you even if you’re AA, whereas in the typical middle market aa, the only expenses you have ahead of you would be AAA interest and a senior management fee. Maybe there’s a little bit of other operating expenses, but it wouldn’t be material. So that rated feeder AA is removed from the assets, has an ABL in front of it, but also the management and incentive fees of the fund take priority as well.

Allan:

That’s exactly right. I think the biggest difference there though is the attachment or the leverage point of the ABL of that senior debt to the rated feeder. So to our earlier conversation on comparing middle market CLOs, when you look at the attachment of a AAA on the middle market, CLO, that’s all the way down to 55 to 58% advance rate. A lot of the rated feeders, certainly on the AA side that are being issued, the senior debt or the ABL is

only the 40 to 50% attachment. So you’re adding incremental subordination

through that senior ABL to the rated feeder to make up or offset some of those incremental expenses and fees that you alluded to.

Shiloh:

So I elicit the cons of the rated feed feeder AA, but the amount of junior capital that supports that is much higher than in the CLO. At the end of the day, they’re both rated AA, so presumably they would’ve the same credit quality.

Allan:

That’s the idea. And I think there’s obviously going to be pros and cons of each, but I think to your point, one of the biggest pros is the added subordination that exists for the rated feeder notes. In comparison to middle market CLOs.

Shiloh:

Let’s maybe just also compare owning middle market equity directly versus owning it in the rated feeder. What are some of the key structural differences there?

Allan:

So I think some of the key differences when you think about rated feeders to middle market CLOs is I like to think about rated feeders, really, they combine both the warehouse period for a middle market CLO and the term securitization. So when you think about a middle market CLO, as we

talked about, there’s a warehouse period that exists that equity has to come

into, the manager has to originate assets and you’re ramping assets over an

extended period of time, and then ultimately waiting for the securitization or

the long-term financing structure of that pool of loans or what’s the most

optimal time to do that. On the rated feeder side, it really combines both of

that warehouse structure as well as the term structure into one. And it does

that obviously through the fact that the notes are issued in delayed draw form. So the senior notes integrated feeder are typically done in delayed draw

fashion. So that allows the portfolio of the fund to be ramped up on a consistent basis, but also being able to draw that leverage as assets are contributed, whereas a middle market CLO is going to be fully funded or fully drawn day one. So that’s I think one of the bigger difference. The other is when you think about middle market assets, there’s a large delayed draw and revolver component that comes alongside those assets, whether those are being contributed to the fund or a middle market CLO, the manager has to find solutions for those. And in a middle market CLO, you’ll typically find

portfolios anywhere from five to 10% in delayed draws and revolvers, and that’s a drag to equity at the end of the day. In terms of having to cash

collateralize a portion of those assets in the vehicle. With the rated feeder,

you’re going to have a similar delayed draw and revolver component to the

portfolios. But the ABL line, the bank ABL line that we’ve talked about

functions as a revolver, so it’s more of an optimal solution to fund those

assets. So there’s going to be less negative drag or less negative carry on the

fund and ultimately the rate of feeder than there would be in a middle market

CLO.

Shiloh:

One other structural difference that we haven’t really talked about is just that in the middle market CLO, it’s almost exclusively firstly in senior secured loans. So the spreads are going to vary a little bit, but it’s three months sofa plus five to five and three quarters on the high end, whereas in the rated feeder, the underlying BDC or fund might be something more like 85% first lien, and then there’ll be a fair amount of second lien or pref or some other funky stuff there. The asset pools do look a little bit different.

Allan:

For sure, the rated feeder depending on the fund, but most of the funds that are utilizing the structure, there’s a lot more asset flexibility associated with it. So there’s the ability not only at the outset, at the original ramp, to be opportunistic in certain maybe non-first lien assets or recurring revenue, which are a big part of a lot of direct lenders. Today is obviously a key differential where middle market CLOs you’re required to be 95% first lien highly diversified. You have obviously collateral quality tests or other items that the managers have to manage too. So there is a lot more asset flexibility that’s allowable in rated feeders, and I think that’s at the outset, but also as the portfolio evolves and as there’s market dislocation, managers have slightly more ability to take advantage of that asset flexibility over time.

Shiloh:

So then moving back to we were comparing and contrasting

the middle market AA and the rated feeder AA, which should offer a higher

return, in your opinion?

Allan:

The rated feeder AA should offer more return to the investors for a couple of reasons. One, there is more structural complexity associated with it, and that’s in the form of obviously the delay draw that we’ve talked about. The investors have to bear the delay draw component of those structures, and with that, the notes have to be issued in physical form. So there’s some operational burden on investors there.

Disclosure:

Note physical form means the notes are not owned electronically. Rather a notarized paper is evidence of ownership.

Allan:

There’s obviously the asset flexibility point that we talked about as well, which is a little differentiated, but then there’s the liquidity point. I think middle market CLOs have established themselves as a fairly liquid asset class at this point. They made up about 25% of the overall CLO market last year. So the acceptance of that structure across the board for investors has been broad. We’ve seen the spread basis between middle market and broadly syndicated tighten over the past 12 to 24 months. So I’d say a lot of the juice or a lot of the incremental spread for investors has come out of that. So rated feeders are a way for investors to gain some incremental spread with some of those trade-offs around liquidity, complexity, et cetera. But we obviously touched on some of the pros, the parts of ordination that we talked about being obviously a key benefit. There’s also typically a longer on-call period associated with the rated feeders, and so there are some obviously structural positives away from just the spread component that investors obviously consider and take into account.

Shiloh:

So then if we are talking about CLO equity versus rated feeder equity, would a lot of your points from the AA be relevant there where it’s a newer structure, people need to do work on it and understand it and are asking for a premium or asking to get paid a little more for doing the work, but at the same time, you’re less levered through the rated feeder?

Allan:

Yes, you are less levered through the rated feeder.

Shiloh:

So from the perspective of equity, maybe the returns model out the same because the equity investor needs to do some work, understand a new structure, but on the other hand, there’s less leverage in the rated feeder

and then maybe another con or pro, depending on how you look at it, would just be that the asset quality of the underlying loans might be different from the 95% first lien that you mentioned.

Allan:

That’s right. I think one of the key differences we touched on is obviously there’s more asset flexibility, and I think over the life of these vehicles while CLO, you’re constrained in 95% first lien, the asset flexibility given into the rated feeders over the course of a four year reinvestment period. I think there’s a lot of optionality that exists for rated feeder equity there. So I think managers have the ability to take advantage of market dislocations, of market changes, opportunities like we talked about in second liens or recurring revenue, that might come up over the course of that period that managers would not necessarily have in a more structured middle market CLO. So certainly I think the less leverage is critical, but I think one of the bigger, more interesting dynamics that we haven’t necessarily seen totally play out yet is that asset flexibility and how managers are able to leverage that to the equity’s benefit over the life of the deal.

Shiloh:

Maybe I missed it or not fully understanding, but when you say asset flexibility, you’re talking about the ability to have more second liens or other funky stuff,

Allan:

The ability to have more non-first lien assets. I won’t use funky assets, but more differentiated assets because I think one big aspect of the market is you think about second liens, there are periods of time where second liens are not that attractive or not that in vogue for managers, but there’s other times where there’s a lot of opportunity in that part of the market to pick up incremental spread for pretty attractive assets. And the same goes for recurring revenue. There’s going to be periods of time where there’s a lot of opportunity to do that in periods of time that there’s not. So the asset flexibility or the ability for the manager to really pick their spots across different parts of the market is more available on the rated feeder side.

Shiloh:

And then one last question is just should the market

expect to see a lot of new rated feeders? Is this a structure that’s going to

gain in popularity over time?

Allan:

We certainly think so. We’ve put obviously a lot of resources into the market. You’ve seen there be a slow start to the issuance of rated feeders, but I think certainly as the market develops, as the investor base continues to grow, as the process for execution of rated feeders becomes more streamlined, I think there’s definitely the anticipation that there will be incremental issuance of the product. It’s not that dissimilar to middle market CLOs 20 years ago when there was only a handful issued annually, and that’s obviously grown. I think this is a market that has the ability to really grow, maybe not to that scale, but certainly to become a large part of the overall private credit financing market over the next few years.

Shiloh:

Great. Well, Allan, thanks for coming on the podcast.

Really appreciate it.

Allan:

Thanks, Shiloh. Thanks for having me.

Disclosure:

The content here is for informational purposes only and should not be taken as legal, business, tax, or investment advice or be used to evaluate any investment or security. This podcast is not directed at any investment or potential investors in any Flat Rock Global Fund.

Definition Section

AUM refers to assets under management

LMT or liability management transactions are an out of court modification of a company’s debt

Layering refers to placing additional debt with a priority above the first lien term loan.

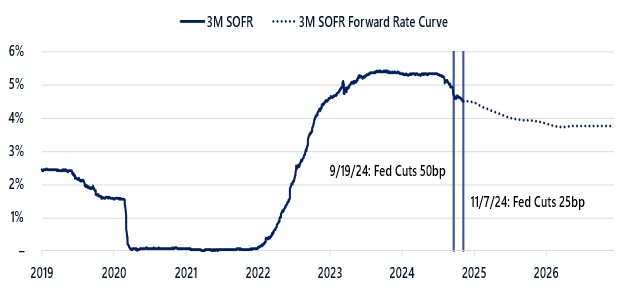

The secured overnight financing rate, SOFR, is a broad measure of the cost of borrowing cash overnight, collateralized by treasury securities.

The global financial crisis, GFC, was a period of extreme stress in global financial markets and banking systems between mid 2007 and

early 2009.

Credit ratings are opinions about credit risk for long-term issues or instruments. The ratings lie on a spectrum ranging from the highest credit quality on one end to default or junk on the other. A AAA is the highest credit quality. A C or D, depending on the agency issuing the rating is the lowest or junk quality.

Leveraged loans are corporate loans to companies that are not rated investment grade

Broadly syndicated loans are underwritten by banks, rated by nationally recognized statistical ratings organizations and often traded by

market participants.

Middle market loans are usually underwritten by several lenders with the intention of holding the investment through its maturity

Spread is the percentage difference in current yields of various classes of fixed income securities versus treasury bonds or another benchmark bond measure.

A reset is a refinancing and extension of A CLO investment.

EBITDA is earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation,

and amortization. An add back would attempt to adjust EBITDA for non-recurring items.

General Disclaimer Section

References to interest rate moves are based on Bloomberg

data. Any mentions of specific companies are for reference purposes only and

are not meant to describe the investment merit of or potential or actual

portfolio changes related to securities of those companies unless otherwise

noted.

All discussions are based on US markets and US monetary and fiscal policies. Market forecasts and projections are based on current market conditions and are subject to change without notice. Projections should not be considered a guarantee. The views and opinions expressed by the Flat Rock global speaker are those of the speaker as of the date of the broadcast and do not necessarily represent the views of the firm as a whole.

Any such views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions, and Flat Rock Global disclaims any responsibility to update such views. This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research, or investment advice. It is not a recommendation offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. Neither Flat Rock

Global nor the Flat Rock Global speaker can be responsible for any direct or

incidental loss incurred by applying any of the information offered. None of

the information provided should be regarded as a suggestion to engage in or

refrain from any investment-related course of action as neither Flat Rock

Global nor its affiliates are undertaking to provide impartial investment

advice, act as an impartial advisor, or give advice in a fiduciary capacity.

Additional information about this podcast along with an edited transcript may

be obtained by visiting flatrockglobal.com.